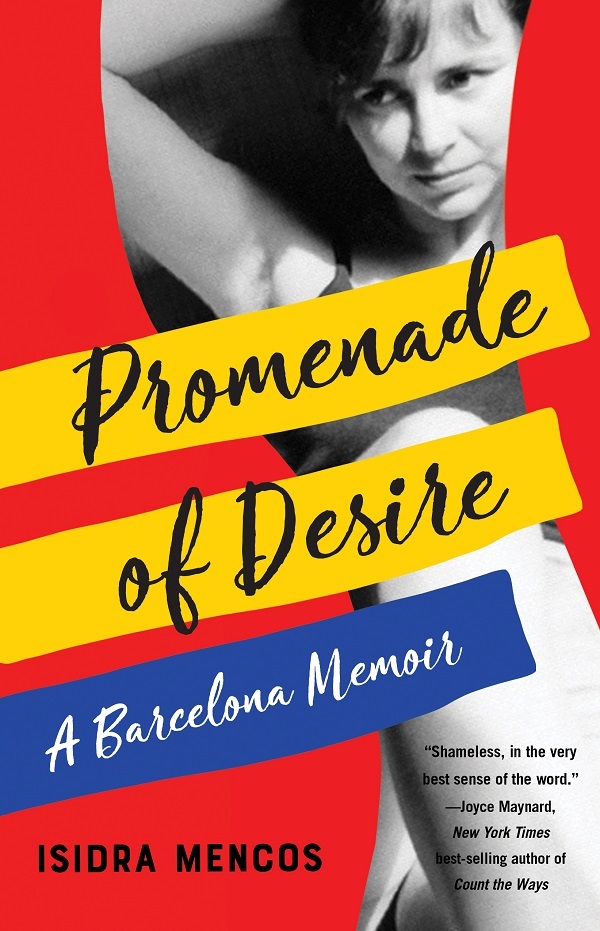

Interview with Isidra Mencos, Author of Promenade of Desire, A Barcelona Memoir

By Luis Medina

Isidra Mencos is the author of the engrossing, page-turning book, Promenade of Desire, A Barcelona Memoir. This book is a frank, honest and revealing coming of age story as a young woman in the transitional period marking the end of the Franco dictatorship to political freedom in Spain. It chronicles her formative experiences growing up with her family, embracing her sexuality, her relationships with men, discovering her liberation through Salsa music and finding herself.

LM: In your memoir Promenade of Desire, you describe your fascination with Salsa music as a liberating force during your coming of age as a young woman. Why Salsa music?

IM: I grew up in Spain under a dictatorship closely allied to the Catholic church. It was a very repressive atmosphere, not only politically but also culturally and sexually. From a very young age I learned to associate sensuality and pleasure with shame and guilt, so I felt disconnected with my body.

When the dictator died in 1975, I was 17 years old and in college. Spain transitioned to democracy and the culture went from repression to liberation and hedonism. That’s when I discovered Salsa music and dancing. From the moment I heard Salsa for the first time, I knew it was the music I had waited for my whole life. Although I didn’t know the steps, I was instinctively in sync with the beat.

Salsa allowed me to reconnect with my body and my sensuality in a guilt and shame-free way. It opened the door to a new me, a young woman aware and accepting of her body’s needs and desires. I fell in love with the great Salsa icons of the 70s, from the Fania All Stars to Rubén Blades, and Los Van Van. I went dancing three or four nights a week, until 5 a.m. I couldn’t get enough.

Salsa scene in the eighties

LM: What was the nascent Salsa scene like in Barcelona in the eighties?

IM: Salsa was not yet popular in Barcelona, where I grew up. Spain had been very isolated from other countries during the dictatorship and did not have significant immigration until the mid-70s so the exposure to this music had been limited. When I started dancing in 1977, there was only one dump of a club in the red light district, appropriately named Tabú, full of seedy characters. I was there all the time.

In the 80s Salsa started to gain traction and a few other places popped up. A very famous one at the time was Bikini, which was in a more bourgeois, safer area, and had two rooms, one for Salsa and one for Rock. Every single night the DJ would end the gig with “Todo tiene su final” with Hector Lavoe and Willie Colón. I loved it.

By the time I left Spain in 1992 there were four or five clubs dedicated to Salsa, and live concerts with iconic figures had started to come to the city. There were also Catalan bands that played salsa standards, like Orquesta Platería and others.

LM: What was the popular music in Spain at that time?

IM: Rock and punk were the most popular. Punk represented the rebellious spirit of the youth, who had grown oppressed and now had the freedom, in the new democracy, to be outrageous and excessive without consequences. A very famous punk group was Alaska y the Pegamoides.

LM: Your ex-boyfriend Abili was a prominent pioneer in promoting Salsa Music in Barcelona during that era. Can you describe the triumphs and challenges that he had promoting Salsa music?

IM: Abili had fallen in love with Salsa before me. He was a journalist by profession and had come into some money due to a labor dispute. He decided that he would invest that money into making Salsa as popular as any other type of music in Barcelona. He produced concerts with Salsa greats like Rubén Blades, Eddie Palmieri, Ray Barreto, Luis Perico Ortiz and others, who came to Spain for the first time. Unfortunately, he was a bit ahead of his times. There wasn’t still a big enough audience to fill in the venues, and he lost a lot of money. That said, he was a major contributor to popularizing Salsa in Barcelona. For example, he ran a weekly Thursday salsa night for a few years at a club, with a live band (Catalan players) and a DJ, and you could see the club filling up more and more every week.

He later got involved with one of the major Salsa spaces in Barcelona, El Antilla, programming the live bands and promoting the scene.

LM: You have visited Barcelona throughout the years since you immigrated to the United States. What are the differences that you have seen in the Barcelona salsa scene?

IM: Salsa is now very well established in the city, in part due to the increasing numbers of Latin American immigrants who started coming in the 80s and the 90s. There was a big wave of Cuban immigration starting in the 90s which changed the direction of Salsa in the city, making timba and rueda very popular, for example.

Salsa was also taken on by several bands which mixed Catalans with Latina American immigrants, and produced great music, such as Lucrecia or, nowadays, Tromboranga.

That said, when I go back now I notice that there are less venues that offer live bands on a regular basis. It’s more of a DJ scene with dance instructors.

LM: In the book, you described Salsa music as a passionate force in your life as you dealt with your family, relationships with different men, sexuality, and the transition in Spain from Franco’s era of dictatorship and repression to freedom and democracy. What do you want the reader to take from reading your book?

IM: I think we all have repressed one or more parts of ourselves from childhood on, in order to be accepted by our parents, our teachers, our friends, our bosses…. My memoir is an inspirational tale about finding a way to reclaim the parts of yourself that have been hidden and becoming a whole person again.

Read also: The multifaceted artist Yamila Guerra and all her projects