North America / USA

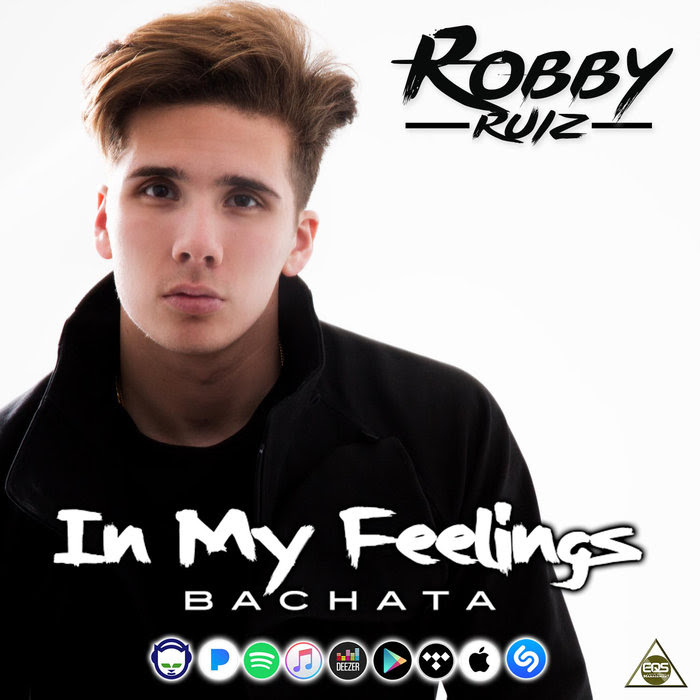

Robby Ruiz Launches his Bachata Single “In my feelings”

The moment´s revelation of Tropical Music brings a theme that will vibrate the deepest emotions

Para ser ubicado en: South – South Atlantic – Florida- Miami

Robby Ruíz is the newest EQS Music´s young artist, and “In My Feelings” is his first song and marks his debut as a Bachata revelation singer. This single is an original cover track by Canadian singer, Drake. The theme of this song is about relationships and how the the main character of the story finds himself in a power struggle with his feelings. “In My Feelings” from Robby Ruíz is an amazing Bachata Remix.

Release Date: July 20th, 2018

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=py6x_Pa7HCY

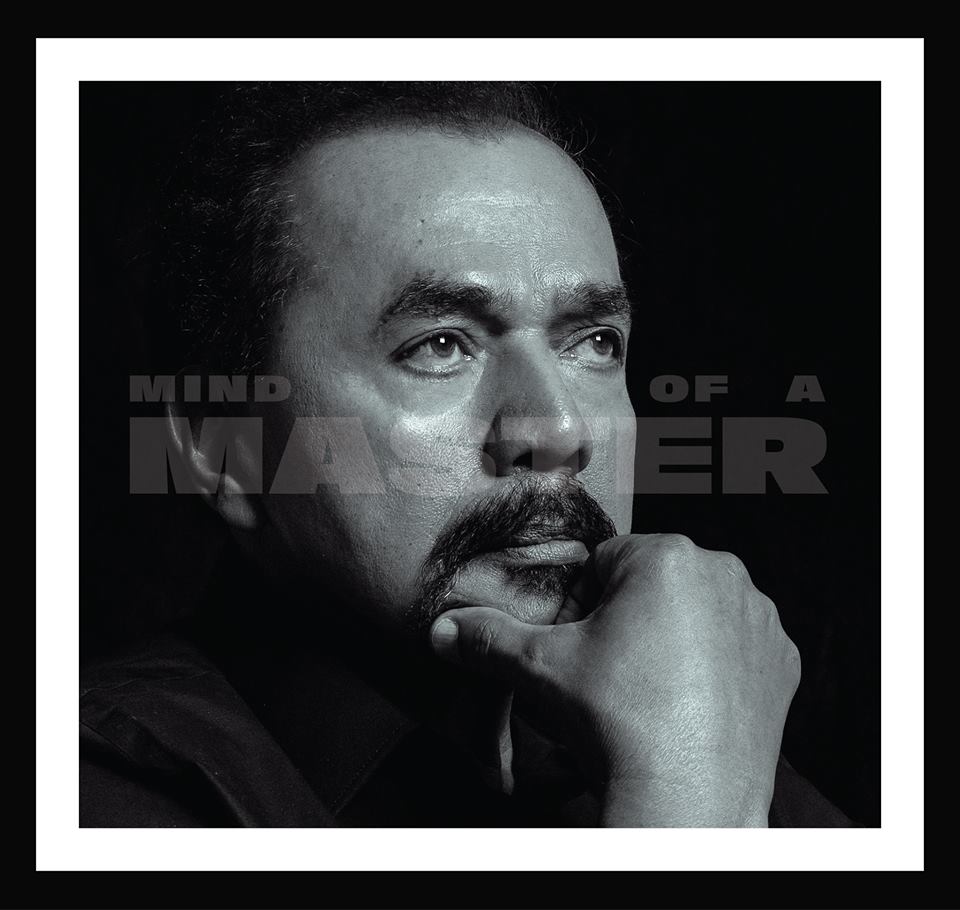

Bobby Valentin’s new album “Mind of a master” is already here!

An Authentic Work of Art to Collect

To be located in: NORTHEAST – MIDDLE ATLANTIC – NEW YORK

The new Latin Jazz Album “Mind of a Master” by Bobby Valentin & The LJ’s is the current sensation of the Latin musical Market containing important collaborations of international renowned figures in 11 tracks. Since its release this recording has marked a precedent with hundreds of unloads in four months by the world fans that support it and you will be able also to be part of that, by downloading “MIND OF A MASTER” in all digital platforms!!!

Release Date: April 14th, 2018

| Credits: | |||

| Bobby Valentin | Arrangements & Bass | ||

| Eliut Cintron | Trombone | ||

| Angie Machado | Trumpet | ||

| Ángel Luis Torres | Alto – Sax | ||

| Eduardo Zayas | Piano | ||

| David Marcano | Battery | ||

| Javier Oquendo | Congas | ||

| Special Guests: | |||

| Iván renta | Tenor – Saxo | ||

| José Nelson Ramírez | Hammond Organ | ||

| Orlando Santiago | String Sets | ||

| Tracks: | |||

| 1. De Nuevo a la Carga | 7.El Cumbanchero | ||

| 2. Latin Gravy | 8.Mellow Funk | ||

| 3.Orocoa | 9. Endless Love | ||

| 4.Smooth Ride | 10.Freedom | ||

| 5.Blast Off | 11. God Bless the Child | ||

| 6. Coco Seco | |||

“Thanks to all the media and the public for the support they have given me in my new Latin Jazz CD, Mind of a Master”. Bobby Valentin

Roberto Valentin, better known as Bobby Valentin, was born on June 9th, 1941 in Orocovis – Puerto Rico. His father taught him to play the guitar at a young age. When he was 11 years old, he participated in a local talent contest with a trio that he had formed. He played the guitar and sang for the trio and they won the first place prize. In 1963, Valentin joined Tito Rodriguez and traveled twice with Tito’s orchestra to Venezuela. He also made musical arrangements for Tito and at times for Charlie Palmieri, Joe Quijano, Willie Rosario, and Ray Barretto.

Bobby was also the musical arranger for the Fania All Stars, and is featured in a live recording of the conglomerate’s song “Descarga Fania” (which he also wrote) playing a bass guitar solo. In 1975, He left Fania and founded his own record label “Bronco Records” and released the album “Va a la Carcel” Vol 1 and Vol 2, recorded “live” at “El Oso Blanco”, Puerto Rico’s oldest state penitentiary.

During the years Valentin has been featured in recordings (and occasional live performances) by Larry Harlow, Ismael Miranda, Roberto Roena, Cheo Feliciano and the always remembered, Celia Cruz.

For more information contact him through this social channel: https://www.facebook.com/Bobby-Valentin-660486604066057/ or visit him in his official webpage: http://broncorecordsinc.com/

Video: https://www.facebook.com/660486604066057/videos/1325583834222994/