Major guests joined the historic Sonora Ponceña concert, which was held on Saturday, November 1, 2025, at the Roberto Clemente Coliseum in San Juan, Puerto Rico, to mark the 70th anniversary of the musical career of one of the most important orchestras in the salsa scene.

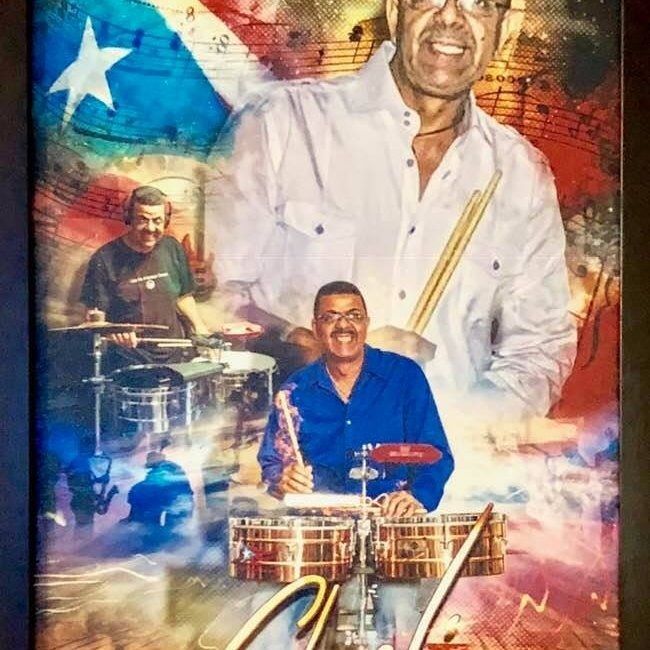

The concert kicked off with a performance by the virtuoso timbalero, singer, and orchestra director Manolito Rodríguez. His orchestra, La Zónika, set the venue on fire with refreshing versions of ‘Encántigo’, ‘Sin tu cariño’ (Without Your Love), ‘Nina’, ‘Antillana’, ‘Maestro de rumberos’ (Master of Rumba Dancers), and ‘Piano man’. It’s worth noting that Manolito was part of “La Ponceña” from 2004 until the end of 2007.

Once La Zónica had warmed up the coliseum stage, the Sonora Ponceña began to deliver its repertoire, which included ‘Prende el fogón’ (Light the Stove), ‘Ñáñara cai’, ‘Ramona’, ‘Boranda’, ‘El rincón caliente’ (The Hot Corner), ‘Tumba Mabó’, and ‘Las mujeres son de azúcar’ (Women Are Made of Sugar) sung by Daniel Dávila; ‘Como amantes’ (Like Lovers), ‘Como te quise yo’ (How I Loved You), ‘Sigo pensando en ti’ (I Keep Thinking of You), ‘Timbalero’—which allowed the timbal player to dedicate himself to the instrument with a spectacular solo, ‘Fuego en el 23’ (Fire in ‘23), and ‘Luz negra’ (Black Light) performed by Darvel García. In fact, shortly after Darvel performed ‘Como amantes’, he was in charge of welcoming the pianist, composer, arranger, and director of the Sonora Ponceña, Papo Lucca, who enjoyed the concert from the stage in a wheelchair.

The rotation of the repertoire allowed for a dynamic interspersing of performances by the guests whom the concert production granted access to the celebration.

With 90 years of sabor (flavor/soul) and salsa, Luigui Texidor, who left the Sonora Ponceña in 1973, returned smiling and grateful. Texidor, who recently received the welcomed honor of seeing his name mark the street leading to Colonia Las Flores in Santa Isabel, his hometown, sang ‘El pío pío’, ‘Bomba carambomba’, and ‘Noche como boca de lobo’ (Night Like a Wolf’s Mouth / Pitch-Black Night).

Sharing that same celebratory vibe, one of the most remembered voices of “Los gigantes del sur” (The Giants of the South), Yolanda Rivera, who was part of “La Ponceña” until 1982, was heard. Rivera proudly recalled her seven years as a member of the orchestra while thanking the invitation to the historic concert, where she performed ‘Hasta que se rompa el cuero’ (Until the Skin Breaks), a track that featured a powerful bongo solo.

Omar Ledée performed ‘Remembranzas’ (Remembrances), originally recorded in the voice of his father, the late and ever-remembered Toñito Ledée, whom Omar represented in a heartfelt posthumous tribute.

Another fan favorite of the Sonora Ponceña followers is Pichie Pérez, who joined the group in 1983 “in substitution of Miguelito and Yolanda.” The singer performed ‘Te vas de mí’ (You Leave Me) and the updated version of an emblematic track, which for the celebration was titled ‘Jubileo ‘70’ (Jubilee ‘70), and which Pichie himself describes as “one of ‘La Ponceña’s’ iconic tracks and the first unreleased track I recorded.” The vocalist was associated with the orchestra for three decades, from 1983 to 2013. Since his departure, he has been promoting his solo career, making this the first time in 12 years he was heard live with his “alma mater” orchestra.

Wito Colón, who left the Sonora Ponceña 15 years ago, arrived ready to sing ‘Hachero pa’ un palo’, ‘Vas por ahí’ (You Go Around), ‘Yaré’, ‘Yambeque’which interspersed a powerful tumbadora (conga) solo, and ‘Sola Vaya’ (Go Alone), the latter song performed with Daniel Dávila and Darvel García. The vocalist was hailed by concertgoers as “the champion of the night” for his vocal power, as well as his charisma before the ardent audience.

Undoubtedly, it was an unforgettable night.

Also Read: Bella Martinez, the irreverent Salsa writer