Jazz virtuous will offer a series of concerts from June to November

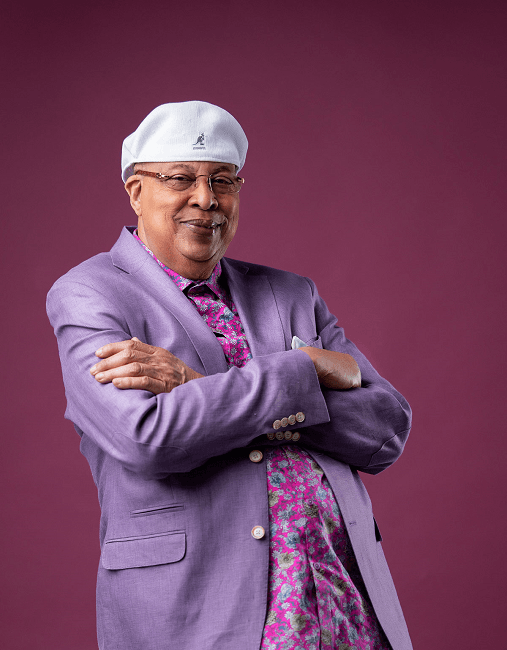

Paquito D’ Rivera and Chucho Valdés

The pianist, composer, and conductor Jesús “Chucho” Valdes and the saxophonist, clarinetist, and composer Paquito D’ Rivera come together again to offer a tour called Reunión Sextet.

This tour of 2022 begins at the Mastercard Jazz Festival (Puerto Rico) and will pass through Poland (Bielsko-Biala), Spain (Pamplona, Marbella, Madrid, and Girona), and Germany (Essen) in June and July, and will end on November 30th in Zurich, Switzerland. Tickets range from €25 – €65 and you can get them in advance on Chucho Valdés’s website. www.chucho-valdes.com

The history of this long friendship dates back to the 1960s when they began their musical partnership as partners in the Havana Musical Theater Orchestra and the Cuban Modern Music Orchestra. With the founding of the Irakere orchestra by Maestro Valdés in 1973, Chucho and Paquito worked together again promoting the fusion of elements of Jazz, Classical music, Rock, and Afro-Cuban music that meant a transcendental development in Latin Jazz, and where Paquito and Chucho were the key figures. “Paquito was the heart of Irakere,” Chucho said.

Eight years later, Paquito went into exile in Madrid and later moved to New York. He developed a successful career as a leader & composer and won recognition as a Jazz Master from the National Endowment for the Arts of the United States in 2005. At the same time, Paquito also maintained his passion for classical music, receiving a Guggenheim Scholarship and commissions for quartets of strings, chamber groups, and symphony orchestras.

Meanwhile, Chuco remained in Irakere until 2005. He led trios and quartets, and established himself as a solo pianist. He produced his most recent production La Creación, a three-movement suite for small ensemble, voices, and Big Band. The masterpiece had its world premiere on November 5th, 2021, at the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts in Miami and after was presented in Lyon, Paris, and Barcelona.

Now, after four decades, they come together to present Reunión Sextet accompanied by an extraordinary ensemble that includes Diego Urcola (Trumpet), Dafnis Prieto (Drums), Armando Gola (Bass), and Roberto Vizcaino Jr. (Conga). The repertoire will include old Latin Jazz hits, Latin American classics, and new compositions from the I Missed You Too album.

The two Cuban virtuosos have accumulated more than 25 Grammys and Latin Grammys. “I’ve always had the hope of being close to Paquito again and playing with him again,” he said. “I’ve always had that hope. Well, this is our moment.” The Maestro Chucho expressed.

His first tour in Spain was in 1981

Chucho Valdés, an icon of modern Afro-Cuban Jazz, told for a digital medium that practices the piano from six to eight hours a day. During the confinement, he was in Florida and composed La Creación (a tribute to Olodumare, the god of the Yoruba religion). This instrumental musical gem is sung, composed, directed, and performed by Valdés, and tells the story of the meeting of Afro-Cuban music in the Caribbean and the United States and how this has influenced globally. He also composed minor works and dedicated part of his time to teaching and virtual concerts.

Likewise, he added that the country that he would contemplate for a possible retirement would be Malaga (Spain) because his great pleasures come together: the Mediterranean, the diet, and many friends in the city.