Search Results for: salsa

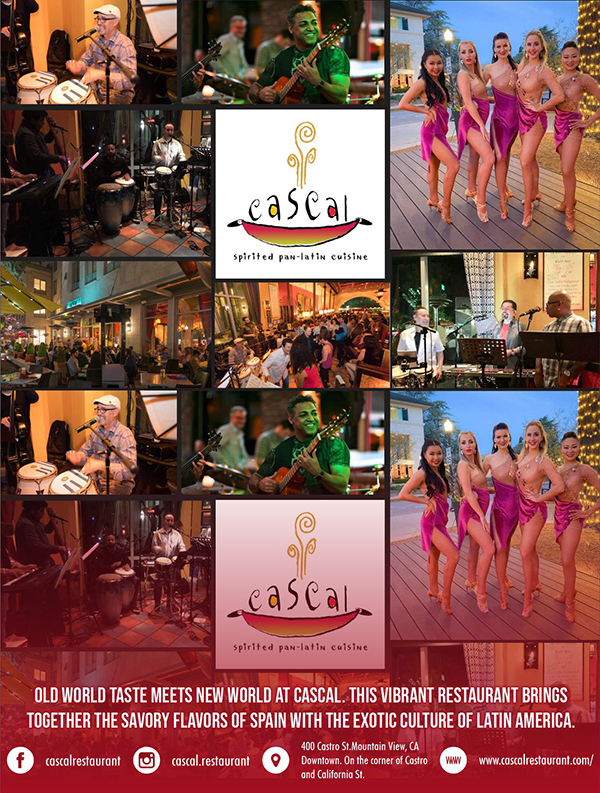

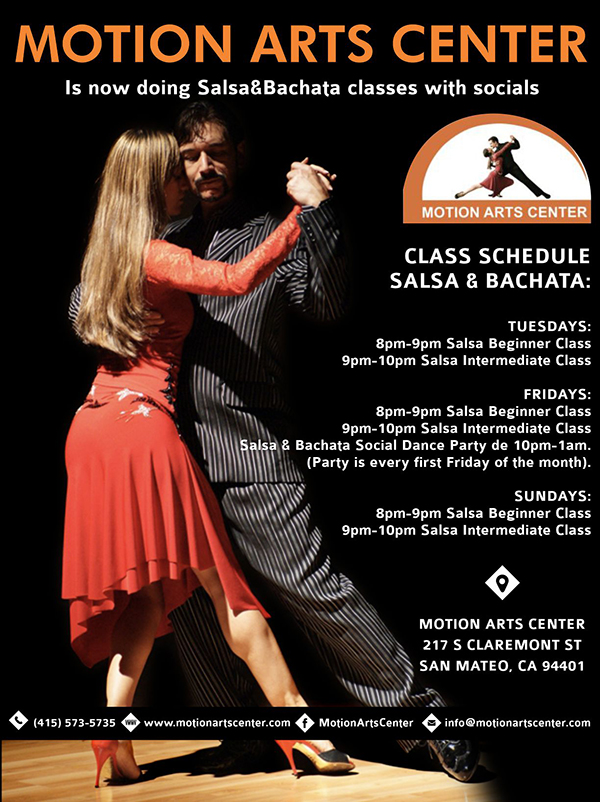

San Francisco Peninsula

Bill Martinez

José Luis Pietrini Silva

José Luis Pietrini Silva was a painter and sculptor and entered into writing. He was born in Venezuela, Monagas State, in the emblematic town of Caripe on August 6, 1922.He studied at the School of Plastic and Applied Arts, at the Cristóbal Rojas School in Caracas. In 1937 he won the first prize of the competition sponsored by the newspaper La Esfera. From then on he participated in countless collective exhibitions until in 1976 he held his first solo exhibition in the Public Area of Electricity of Caracas and in 1996 he founded the first Gallery of Permanent Art of the State of Monagas, where he soon received the Municipal Prize of Culture in Plastic Arts being awarded the Medal of Honor to the Mér. in his second class by the mayor of Caripe in 1999.

National pride who values him for his creative trajectory and guides the students of plastic arts “to see something beautiful in a stone, in a little bit, that another does not see it” possessing an extensive and solid work framed within the canons of realism and his love for the Venezuelan landscape where the brilliant handling of color, light and texture “C Visual chronicler par excellence, he paints what he sees and feels.”

Unfortunately, on January 6, 2014, at 91 years old, Master Pietrini left in Caracas, leaving a great legacy throughout the national artistic field.

International Salsa Magazine, thanks the Pietrini family, especially their son the engineer Luis Prietrini who kindly provided us with the work of their private family collection.