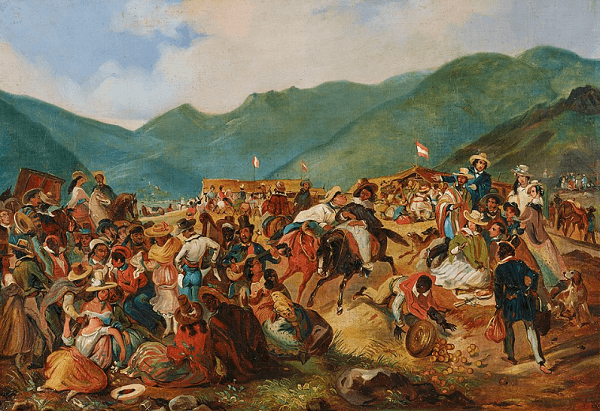

In the year after the big war ended, a terrific hurricane tore across the island, and in the town of Santa Barbara de la Loma the Catholic church was destroyed, but the modest compound of Senora– devotee of the seven powers and gifted daughter of Yemaya, spirit of the seas – went untouched by the storm. The people of Santa Barbara were not surprised. They called Senora “La Poderosa,” the powerful one, for she could heal the sick better than doctors, break and cast spells – but only for good – and see beyond the now and here. Believers in the natural religion came weekly to the walled yard behind her neat, two-room bohio to praise the mighty spirits who might possess them as they danced and chanted to the inspired drumming of the tumbadores.

On the next full moon, Senora called her gente to a special midnight ceremony. Dressed as always in immaculate white robe and turban, smoking a long cigar and swigging from a flask of rum, she told the assembly that Hate was hard at work everywhere, and worse things than hurricanes or even the war just fought were soon to come. Now they must all concentrate their prayerful energies and send goodness in the guise of music to an evil world. The native rhythms of their island, produced from the potent mix of slaves, colons, and indios, could bring people of all kinds and colors together. As dark hands beat out on taut skins a deep, steady roll like distant thunder, Senora called up into the moonlit sky: “May the babies born of Mambo be bringers of justice and peace where there is none! Go, my Mambo! Go now and work your musical magic at the center of the biggest city in the strongest nation on the earth!”

And the Mambo went and did all this, and much, much more…

Story goes that a certain midtown Manhattan dancehall was dying a slow death at the tag end of the Big Band era, just after the so-called “Good War.” The guy who was managing this musical venue (maybe for the Mob) was bemoaning the lack of customers to a canny Broadway promoter who poked a sallow finger at the bemoaner and said “Hey! If you don’t mind spics and

niggers in the joint, I can fill it six nights a week!” “At this point I don’t mind if it’s spics, niggers, or little green men!” “Done deal!”

Twas the season of Jackie Robinson “integrating” baseball’s major leagues. Smart money knew that American apartheid couldn’t last forever, at least not overtly. And where else would the winds of change blow first and hardest but in the Empire City, aka Nueva York? So the Palladium opened with a hot mambo policy, the best Afro-Cuban bands were hired, and lines formed around the block. Harlem and Spanish Harlem were now welcome in a big midtown venue. And not only “spics” and “niggers” showed up, but “wops” and yids” as well, the bridge-and-tunnel “mamboniks.” The word spread, and whitebread cafe-society mavericks came to check it out and stayed to shake a tail feather. For the next couple of decades it was the “place to be, thing to do” in NYC, if you wanted to move to and be sent by the best hot Latin sounds.

Around 1954/’55, the mambo crested in the Pop consciousness, with “Papa Loves Mambo,” “Mambo Italiano,” and “What The Heck is the Mambo?” on the mainstream Hit Parade. Perez Prado even took “Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White” to Number One on the charts. But the real mambo, cha-cha- cha, guaracha, charanga, and son stayed underground, a niche thing, ethnic dance

music for Manhattan Latins and the cool cognoscenti. Raided and harassed by authorities who didn’t cotton to Mambo’s miscegenating powers, the Palladium lost its liquor license in the early ’60s and closed for good in ’66, just as the “new breed” wave of Latin Soul & Bugalu was making noise on the mean streets. And the beat goes on…

The Mamboniks were cool-looking Italian & Jewish guys & gals, out of high school but not in college, who hung out around Dubrow’s on the Hiway. If one of them had a dented sportscar or an old but flashy convertible, they’d congregate around the car at the curb, the dash radio loudly broadcasting Dick“Ricardo” Sugar’s mambo show of an evening, trying out hip-swinging cha-cha steps, casually dap guys and foxy girls in tight skirts; and tho the guys were not really hoods, they’d hang with future felons down the poolroom sometimes, and push a little weed to the hipper highschoolers, who whispered that these guys rolled queers in the Village for bucks and kicks…. but the big kick for the Mamboniks was the Latin Kick, hitting the Palladium at least once a week to hobnob with Ricans and Cubans and dap Harlem dudes and debs, all dressed up in continental suits and cocktail gowns, moving & grooving to the hot, blaring rhythms of Tito Puente and Tito Rodriguez, Eddie Palmieri, Joe Cuba, Orquesta Aragon, the La Playa Sextet, and many more smokin’ outfits who played en clave. Rest of the time they hung outside the cafeteria almost

under the BMT El, hanging on the Hiway but vibing they were too hip for the Hiway, still living at home in Brooklyn only ’cause it was free, but definitely on the way out and on up – or so it appeared to those a few years younger, hung up in mundane Midwood and Madison scenes. I didn’t really know the Mamboniks, but I knew who they were (the distance between 15 and 18 being even greater than between the Hiway and Broadway): one of them would fall with the felons and do time… another would marry his little sexpot cha-cha partner and go into the restaurant business downtown… yet another would become a musician/dope dealer, accent on the dope dealer. I only glimpsed these Mamboniks passing by Dubrow’s, but they called me (while ignoring me) to a more magical city than the one I knew as yet.

Jose de la Subway Speaks of Working the Mountains

There’s one or two agents book all the bands, and you best not get on their bad side! This guy I know from El Barrio, he plays timbales – he’s no Puente but he’s still young – he pulled me into this gig, subbing for the guy who was too fucked up on duji to make the job. We all meet at the bus terminal near the Dixie Hotel on the Deuce. Takes a couple hours to get up there and it’s real country, you can smell the trees! There’s these big Jewish hotels, they all book one Latin band to alternate with whatever square Pop band they got, and of course the biggest hotels get the big name bands and the smaller hotels get the cheaper bands who sometime hire kids just breaking in who look eighteen and can play some but don’t expect no union scale. You got this shack full of bunk beds to crash in, you eat leftover childrens’ meals – if there’s a hip Rican or Soul working in the kitchen you may get extras – and they don’t want to see your face around the place till showtime. Maybe they let you take a rowboat out on the lake, but you best stay away from the pool till you’re sent out there to play a cocktail set. They always call it an ‘Olympic-sized pool’ even if it’s four foot

deep! All these white chicks are out there in bikinis trying to get as dark as the people they don’t want in the pool with them. You play some cha-chas poolside late in the afternoon and you get to check out these chicks, some of them are hot, some give you the eye, but you wear shades and keep a stone face, and of course you’re high ’cause everybody be smokin’ weed in the band, that’s all you do, and you keep the job by keeping your distance from the hotel’s clientele. Some hustling bands be doubling, tearing around those mountain roads from one little hotel to another, making two jobs a night, wearing those ridiculous rhumba shirts with the big ruffled sleeves. After the last set everybody goes to eat and hang at Corey’s Chinese Restaurant in Liberty. When it’s Mambo Night at the Raleigh you sit in. And if you fuck up, or when the contract’s over, you’re back on the Hound to the Deuce, and you don’t have much loot to show for it. You’re paying your dues, you’re getting experience.

Musically, the late ’50s/early ’60s were dynamic times in NYC. Monk with Trane at the Five Spot, Ornette Coleman introducing “the new thing” aka “Free Jazz,” the hard-bop funk of “Moanin’” by Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, “Kind of Blue” by Miles, Trane’s classic quartet coming into its own with “Giant Steps” and “My Favorite Things.” And the Folk boomlet peaking in the Village

with Baez and Dylan, Paxton, Van Ronk, Ochs, and many more. R&B was in a slump and the Top 40 sucked bigtime… but over in Brooklyn and the Bronx, a new generation of Nuyoricans was coming of age, and tho they still dug the Afro-Cuban sounds, the mambo and the cha-cha-cha belonged to the (recent) past, so they were experimenting: Bronx Pachanga was revved-up charanga… trombones lent a harder edge to a conjunto like Eddie Palmieri’s La Perfecta… and “Latin Soul” was Doowop (a big influence en la calle) mated with the bolero feel and the bongo/congas beat. Joe Cuba knew he was onto something when his “To Be With You” (a bolero in English) became a street fave circa ’62/’63. Ace Cuban conguero Mongo Santamaria had a crossover hit of sorts with a jazzy horn chart on “Watermelon Man.” And Ray Barretto charted nationally with a speeded-up charanga featuring a streetwise Spanish rap superimposed: “El Watusi.” The times they were a-changin’ in the barrio. Joe Bataan was “Singin’ Some Soul.” Willie Colon was getting “Jazzy.” Eddie Palmieri’s hot, eight-minute jam on “Azucar Pa’ Ti” was a breakthru, played in its entirety on the radio by Symphony Sid and even by Dick Ricardo Sugar. Pete Rodriguez came on strong with the irresistible “I Like It Like That”… and the Latin Bugalu was a mid-’60s sub-genre (e.g. Johnny Colon’s “Boogaloo Blues”). But by the early ’70s, the newly branded “Salsa” hyped by Fania Records (the Latin Motown) prevailed, and Latin Soul’s swan songs were sung by Ralfi Pagan (“Make It With You”), and Paul Ortiz (“Tender Love & Sweet Caresses,” produced by “Subway Joe” Bataan). Musical artifacts remain, but as for the vibe, “You hadda be there, folks!”

That Latin Thing

The Afro-Cuban sounds, and the extensions and variations on those templates by their New York inheritors, were the hottest and coolest Latin sounds. Musicians have big ears, and there was always cross-fertilization between the seemingly segregated genres of Latin and Jazz (eventually producing – wait for it – Latin Jazz). So why aren’t more jazz buffs, and other musically savvy civilians, into the rich “Spanish Tinge” heritage? (They’ve always been into it in their own way down in Norlins.) Different languages as well as divergent styles, plus the commercial priorities of bottom-line execs who package musical product, perpetuate musically exclusive marketing niches, even unto today. But many stateside Jazz greats especially groovitated towards the Latin

thing. Dizzy Gillespie with Chano Pozo creating Cubop… Charlie Parker’s jams with Machito… Cal Tjader with Eddie Palmieri… Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man” definitively rendered by Mongo Santamaria: these are some of the finest fruits of the Jazz + Latin marriages, and there have been many more in recent years. Yet the hardcore tipico and original classics are still all but unknown to generations of US Americans, and that’s a lowdown dirty shame.

Tio Jonny to the rescue! If you dig rhythms that won’t let you sit or stand still, or love to love a great love song, I’ve got two Latin strains to introduce into your musical bloodstream: superlative slow jams of yearning, ecstasy, betrayal, and loss in the best bittersweet boleros… and hip-shaking, toe-tapping dance classics of musica caliente. Maestro Cachao wasn’t just boasting when he titled one of his signature jam sessions in miniature “Como mi ritmo no hay dos.” There’s nothing quite like this Latin thing. But don’t take my word for it. Go check it out for yourselves, sis & bro!

Musica Caliente 101

Salsa dura? Salsa Brava? Salsa romantica? Such consumer designations are so much caca de toro. To quote el rey Tito Puente, “Salsa is something you put on your food.” As a brand, “Salsa” moved a lot of units for Fania and other smaller labels in their heyday. But it was still music with Afro-Cuban roots, refined (or, purists might aver, debased) by Puerto Ricans and Nuyoricans, as insiders and aficionados well know. It was a music all about rhythm (we’ll consider the beautiful boleros shortly), pegged to the clave beat, where the Afro drums could sing melodiously while the Euro piano, violins, and horns remade themselves into rhythm instruments ( the repetitive, tension-building keyboard montunos, twin charanga fiddles, or twin trombones).

As the music morphed from Havana to New York, it got faster and louder (como no?), but the rhythms certainly didn’t cool down, tho they could sound hot and cool at the same time when vibes were featured, as in the ’50s party classic “Chop Suey Mambo” by Alfredito (Al Levy) or on many jams by T.P., Joe Cuba, or Latin-converso Cal Tjader. Anyone who felt this music in their bodies and souls (which are most definitely not separated in this art) would know this was musica caliente – and, as Ray Barretto titled one of his best workouts: “Que Viva la Musica.”

Say you’ve heard some of the great old school sounds and want to hear more? Tio Jonito is going to start you off with a sampler of the best (or at least some of my favorites) from the great days of this musica caliente, sometime in the late ’40s on into the ’70s. You go online and find these smokers on my list and you’ll not only get a little musical education but you’ll swing your butt off and have a ball. Vaya!

Orq. Casino de la Playa w/Miguelito Valdes: “Bruca Manigua”

Arsenio Rodriguez Orq.: “Dame un Cachito pa’ Huele”

Machito & his Afro-Cubans: “Tanga”

Chano Pozo: “El Pin-Pin” (nice later version by El Gran Combo)

Los Astros: “Que Lindo Yambu”

Arcano y sus Maravillas: “Rico Melao”

Sonora Matancera w/Celia Cruz: “Caramelos”

Sexteto La Playa: “Jamaiquino”

Randy Carlos: “Smoke” (“Humo”)

Fajardo y sus Estrellas: “Ay! Que Frio” (+ jazzy ’70s cover by Ocho)

Cortijo y su Combo w/Ismael Rivera: “El Negro Bembon”

Orquesta Aragon: “Caimitillo y Maranon”

Cachao y su Ritmo: “Malanga Amarillo”

Chappotin y sus Estrellas w/Miguelito Cuni: “Alto Songo”

Mongo Santamaria: “Afro Blue” “Para Ti”

Mongo Santamaria w/La Lupe: “Canta Bajo”

Tito Puente: “Oye Como Va” “Ran Kan Kan”

Eddie Palmieri & Cal Tjader: “Picadillo”

Tito Rodriguez & Orq.: “Mama Guela” “Ave Maria Morena”

Joe Cuba Sextet w/Cheo Feliciano: “El Raton”

Mon Rivera: “Lluvia con Nieve”

Orquesta Broadway: “Como Camino Maria”

Ray Barretto: “Cocinando”

Pete “Conde” Rodriguez w/Johnny Pacheco Orq.: “Azuquita Mami”

Willie Colon Orq. w/Hector LaVoe: “Abuelita”

Eddie Palmieri w/Charlie Palmieri: “Vamanos pa’l Monte”

Boleros 101

Boleros are Latin love songs, and the best are equal to any operatic aria, Broadway show-stopper, or Pop ballad, especially those written and sung from the 1940s through the ’60s, the era of the bolero. Behind even the slowest bolero there’s a rhythmic roll (maintained by bongos, congas, or light timbales taps), analogous to the roll of “r” in spoken Spanish. Can’t abide musica romantica? The bolero, friend, is not for you. Latin America – notably Cuba, Mexico, and Puerto Rico – turned out great boleristas in the epica de oro, and the tunes they sang were world-class, true standards which sound just as strong today as ayer. But leave me not wax rapturous; rather let me share some of my fave boleros with you, and point you YouTubeward to hear them all.

Beny More: “Como Fue” “Hoy Como Ayer”

Olga Guillot: “Mienteme” “Tu Me Acostumbraste”

Trio Los Panchos: “Nosotros” “Sabor a Mi” “Los Dos”

Vicentico Valdes: “Tus Ojos” “La Montana”

Tito Rodriguez: “Inolvidable” “En La Soledad”

Los Tres Ases: “Delirio” “Estoy Perdido” “El Reloj”

Cheo Feliciano (w/Joe Cuba sextet): “Como Rien” “Incomparable”

La Lupe w/Tito Puente Orq.: “Que te Pedi”

Santos Colon w/Tito Puente Orq.: “Ay Carino”

Armando Manzanero: “Mia”

Los Tres Diamantes: “La Gloria eres Tu”

Javier Solis: “Si Te Olvides (La Mentira)”

Los Tres Caballeros: “La Barca” “Regalame Esta Noche”

Los Tres Reyes: “No Me Queda Mas”

Pedro Infante: “Contigo en la Distancia” “No Me Platiques Mas”

Jacaranda Castillon: “La Gata Bajo La Lluvia”

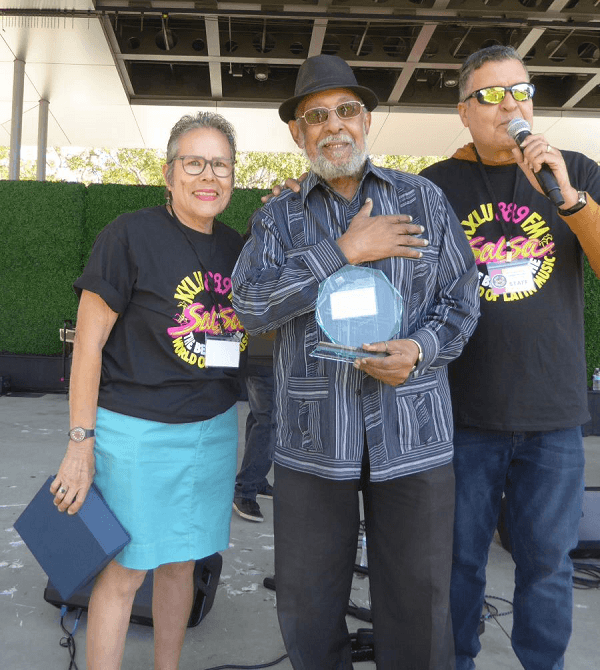

Read also: Dominican bandleader and singer Papo Ross is triumphing in Montreal