Search Results for: Cali

Unity, The Latin Tribute to Michael Jackson

North America / USA /

Unity, The Latin Tribute to Michael Jackson is a testament to the power of music and one man’s indomitable spirit. The passion project of Peruvian-born, Miami-raised producer / multi-instrumentalist / arranger Tony Succar, Unity features more than 100 musicians, such Latin superstars as Tito Nieves, Jon Secada and Obie Bermudez and the mixing magic of Jackson’s legendary engineer Bruce Swedien in the first ever Latin album salute to The King of Pop.

Fueled by his relentless commitment, quiet determination and passionate faith in the loving message behind much of Jackson’s music, Succar has spent the last four years carefully creating Unity: The Latin Tribute to Michael Jackson. He overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles, turning each roadblock into a stepping stone to take the project to new heights. In the process, he married Jackson’s timeless pop and R&B tunes, such as “Thriller”, “Bilie Jean”, and “I Want You Back” to his glorious salsa and tropical rhythms, creating innovative, vibrant arrangements that snap to life with exhilarating energy.

“American funk, soul, jazz – all those styles that were influencing Michael – were inspired from African music”, Succar says. “Same with Afro – Peruvian music, Cuban music. These songs were meant to be. Their original flavor lends itself to these Latin rhythms”.

Succar, 28 grew up listening to his parents play Jackson’s music, and by 13 had begun his own music career. He started on piano and segued to percussion, graduating with a degree in jazz performance at Florida International University in 2008. But it wasn’t until after the superstar’s untimely passing in 2009 that Succar, who earned his Master’s in Jazz performance from FIU in 2010, took a deep dive into the music and the man.

“That’s when I became a fanatic, memorizing all his lyrics” he says. “He was an amazing singer. I started analyzing every single detail”.

As Succar pored through Jackson’s material, revisiting songs like “Man In the Mirror”, “Earth Song” and “They Don’t Care About Us” – all of which are reimagined on Unity – he came to a realization: “Michael wasn’t only a musician, he was a spiritual person. He was speaking to people’s hearts through his music. He was a true role model and leader, not only in the music industry, but life in general”, he says.

Concurrent with his discovery, Succar arranged a salsa-infused version of “Thriller” for a Halloween party at Miami’s legendary, now closed Van Dyke Café. The reaction was so immediate and overwhelmingly positive to the performance of this new arrangement, that Succar recorded a version in his bedroom with his band, posted in online and gave away copies. Djs started playing the track and Succar began getting requests from around the world for a full album of Latin – flavored Jackson songs. “That sparked it”, Succar says. “I was such a fan. I felt like I had to do something”.

He launched a Kickstarter campaign and raided more than $10,000, which allowed him to record basic tracks and the idea and harmonious ideal of Unity was born. “The one thing that stood out in Michael’s usic was love. The reality was unity,” He says. “I also wanted the title to stand for something: a real marriage between Latin roots and American pop culture and to help keep Michael’s legacy alive”.

Part of keeping Jackson’s legacy alive meant incorporating elements of the original production in each of his fresh renditions for Unity. “Even the horn lines, I would transcribe them from Quincy Jones’ produtions and then apply them to the arrangement in a different way,” Succar says. “The essence of every song was respected. I gave it my best to create this very thin line between what Michael did with his production and what I brought to the project”.

As Succar proceeded, an astounding number of coincidences buoyed the project. Succar’s initial plan was to record the album with one vocalist, soulful Broadway veteran Kevin Ceballo, but as Succar finalized the arrangements, the idea of a compilation album cae to him. The first artist he reached out to was legendary salsa singer Nieves. He heard nothing back for months . Then, one day in the studio someone suggested Nieves fo “I Want You Back”. Succar explained he’d had no success contacting Nieves.

It’s turned out a studio visitor knew Nieves, called his manager, sent Nieves an MP3, and within 10 minutes, Nieves was on the phone asking when he should come in to record his vocals.

Nieves became the project’s godfather, bringing in other Latin stars, such as India and Jean Rodriguez. “If it weren’t for Tito, I would never have been able to develop this into what it is, “Succar say. “He really opened the doors for me”. Nieves even brought in his son, Tito Nieves Jr. to duet on the album closer, an emotional take on “You are Not Alone”.

As the project progressed, Succar sought out Secada, but once again, was running into walls. He had switched to a different studio and the recording engineer just happened to have worked wih Secada and upon hearing Succar’s story, gave Succar the singer’s direct email. Secada immediately replied that he wanted to record “Human Nature,” his favorite Jackson track.

But there was more to come. Succar contacted Swedien about mixing some tracks, but failed to get a yes after more than a year’s effort. He met his engineer Nick Valentin through a mutual friend, who piped up that he’d been Swedien some music and next thing Succar knew, he’s sitting beside his hero at Swedien’s ranch as Swedien mixed “Earth Song” and “Smooth Criminal. “He was the cherry on top,” Succar says. “When we were mixing, he would put up the original Michael songs and put on our remixes to compare and contrast. He mixed the tracks on the same Harrison 32C model console he mixed ‘Thriller’ on”.

The groundbreaking album, a joint project between Universal Music Classics, Universal Music Latin Entertainment and Universal Music Mexico, embodies Jackson’s spirit of harmony and bringing diverse cultures together through music.

Where there once was nothing but a dream, Succar now sees unlimited possibilities. Not only will there be a tour to support Unity: The Latin Tribute to Michael Jackson, but he is considering future Unity projects that could salute the music of other timeless artist, such as the Beatles or the Bee Gees, filtered through a Latin musical lens. “Unity is going to become a movement,” he says. And given how far Succar’s come already, who could possibly doubt him?

Cuban singer-songwriter Osmay Calvo shows his versatility in the New Jersey music scene

Osmay Calvo is just one of many examples of why Cubans have triumphed so many times in the United States, which is why his story and that of many of his compatriots always serve as inspiration for those seeking a career in the music industry but who do not dare to do it because of the misfortune of being born in a place that did not offer them the necessary opportunities for this.

Calvo was kind enough to take a few minutes of his time to talk about all that had happened to his career to date, so it is an honor for us to describe what was discussed in the following lines.

How Osmay became interested in music

Osmay tells us that, from an early age, he loved popular music, so he began to participate in school music events when he was just six years old in Tarará, east of the city of Havana. At the same time, his mother enrolled him in singing lessons and he spent much time with his family musicians, including his uncle, singer Pedrito Calvo, who was a member of Los Van Van.

A few years later, he began to attend various types of contests and joined the Mariana de Gonitch Singing Academy, directed at the time by maestro Hugo Oslé, thanks to which he met Pacho Alonso, Ela Calvo, Mundito González, and many other important figures of Cuban popular music.

Official beginning of his professional life

Osmay’s professional start was in Cuba when he joined the Adolfo Guzmán company in 1995, which is when he had his first paid job in music. Although it is true that the Cuban government got a huge percentage of the money earned by the artists, Osmay appreciates the experience and the chance to know other countries through his activities with the company.

Some time later, he had the opportunity to travel to Spain and then to Mexico, where he participated in a music competition and won first prize with the song “La Bamba.” He then spent another month in Spain for an event until returning to Havana and winning the Mariana de Gonitch Singing Contest, obtaining the prize for the great popular generation of national music award, which led him to travel through the 14 provinces of Cuba to offer his services and make himself better known.

Moving to the United States

It was in 2002 that Osmay finally decided it was time to look for other roads and leave Cuba to no longer return. He was going to sign a contract with Mambo Records in Miami, but things did not go according to plan, so he started recording his own music and went to New Jersey, where he began to organise his own orchestra with which he has 16 original songs written by himself, but also numerous covers of hits by other artists.

He has not been back to his native country for about 24 or 25 years. In fact, most of his family also lives in the United States and Canada, except for his uncle Pedro Calvo, some cousins, friends, and his music teachers.

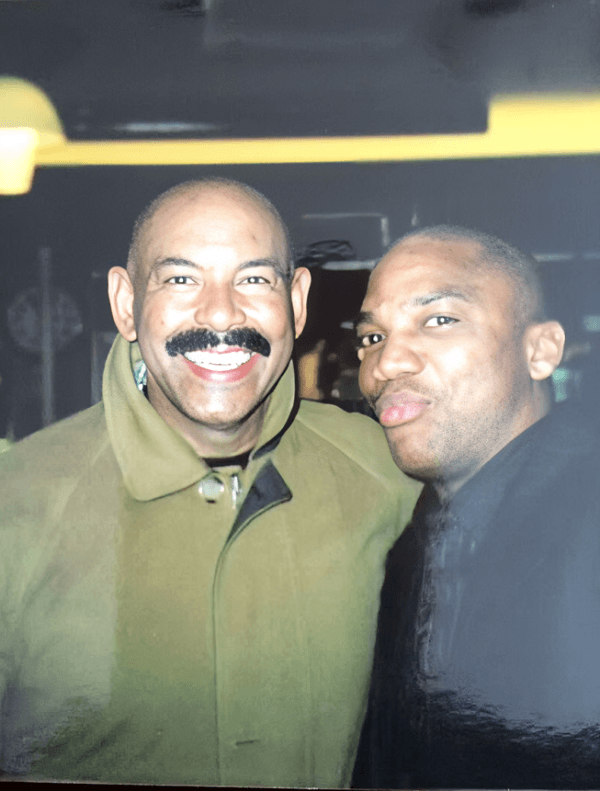

However, after all the time he has been gone, things have not been entirely easy for Osmay, especially in the beginning. The hardest thing for him was language learning and how little he knew about his new place of residence, but the artist quickly learned and was gradually integrated into this new music scene, thanks to which he was able to play with many orchestras and meet great figures such as Oscar D’León at the Coco Bongo Club in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and Fernandito Villalona, for whom he opened one of his shows.

In New York, he played with many bands and learned a lot of music that was played locally. Osmay brought an academic background in lyrical and symphonic singing from Cuba, but New York has mostly restaurants, nightclubs, and fairs, so he had to adapt to a completely new format and audience.

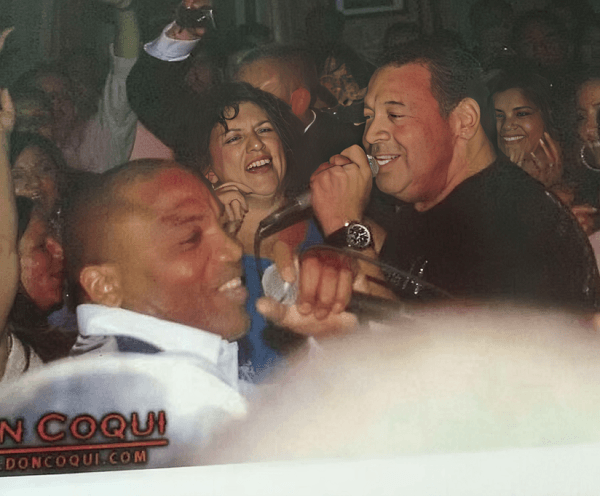

Fortunately, he got it and was recommended by other musicians to play in many places until one night he was asked to play at Don Coqui and was told that Tito Nieves would be there. Then, when it was time for Osmay and nine other musicians to perform on stage, Jimmy Rodríguez, the owner of Don Coqui, approached them to say that Nieves might come and play with them later. A little while later, the Puerto Rican actually did approach with a microphone in his hand, and both he and Osmay began to improvise, and the show lasted until two o’clock in the morning. For the Cuban, it was an exceptional experience and an unforgettable moment in his career.

Haberte Conocido

After all the progress made, in 2021, Osmay felt ready to release his first independent album, which he titled “Haberte Conocido”. This was a goal to fulfill since Hugo Oslé, who was also his singing teacher, told him and the rest of his students that it was very important to be an independent artist who wrote and recorded his own songs.

In addition to that, he remembers that everyone in the class was a bolero singer, so he wanted to do something that would set him apart from the rest, and that is how he began to turn to salsa and other genres. This made him a much more versatile artist who could sing almost any genre coming his way. From then on, he stopped learning the original soneos of the songs and started to improvise on many occasions, which eventually led him to compose. Finally, in 2021, he wrote “Haberte Conocido,” which he put together from ideas that came to his mind and that he saved on his mobile phone during rehearsals. Then, stanza by stanza, he created the first song of his own.

Read also: Multi-instrumentalist Ian Dobson talks about his trips and academic background

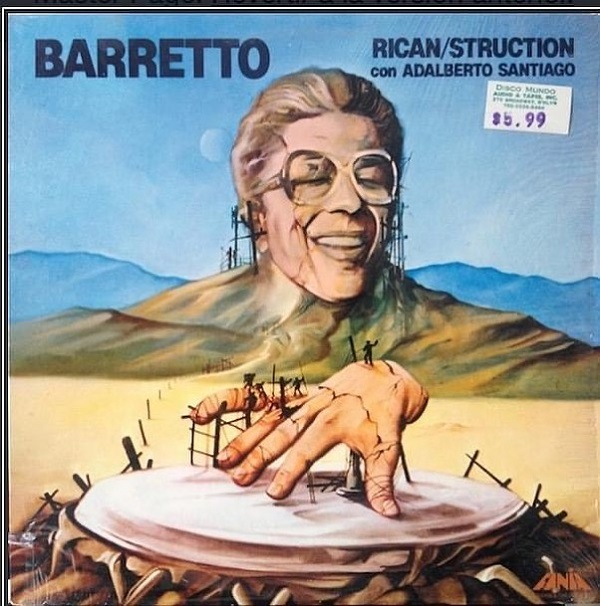

Ray Barretto: Rican/Struction of a Master for the year 1979

“Rican/Struction” is the most representative album of Ray Barretto’s career, not only for its innovative character but also for its immense personal significance.

In 1978, Ray Barretto was struggling to cope with the poor reception of his recent album, “Can You Feel It?” (1978), which he had recorded a year earlier with Atlantic Records. Despite its quality, the album went largely unnoticed by the public, causing Barretto great frustration and disappointment.

For a few years, Barretto had been tired of playing the same old repertoire. To give his career a fresh start, his manager, Jerry Masucci, sold his contract to Atlantic, intending for him to record a more commercial jazz fusion and funk album. However, the plan didn’t work out as they had hoped. During this time, the percussionist spent his days feeling pensive and worried, convinced that signing with Atlantic had been a mistake because the label gave his last two albums very little promotion.

One morning, while driving and lost in thought, Barretto slammed on his brakes to avoid hitting a car that suddenly appeared. The abrupt maneuver caused another vehicle to rear-end him. The collision resulted in several injuries, the most serious being severe damage to the tendons connecting his thumb to the rest of his right arm. Doctors “gave up on him,” claiming he would never be able to play again.

The news plunged the musician into a deep depression. Doctors recommended surgery, but Barretto refused, fearing his hand would never be the same. He sought second opinions in Los Angeles and San Francisco, but every specialist gave him the same diagnosis and the same solution: surgery.

They say Barretto would visit clubs with a palpable sadness and bitterness because he couldn’t play. Many people in the industry said his career was over until one night, an old friend and fellow musician told him about the benefits of acupuncture, a traditional Chinese medicine that had helped several people with similar problems.

Barretto underwent a long and painful treatment for almost two years, gradually restoring movement to his right hand. Once he was nearly recovered, he decided it was time to return to music.

He broke his contract with Atlantic, sought out Adalberto Santiago (who had left his band in 1972 to form La Típica 73), and re-signed with Fania Records. With them, he produced the album “Rican/Struction” (1979), his most representative work, not only for how progressive it was but also for the immense personal value it held.

The production was a resounding success, and a year later, it earned him the titles of “Musician of the Year” from Latin New York magazine. In this way, the master Ray Barretto demonstrated his great strength and tenacity to the world.

Did you know…?

-

The song “Al Ver Sus Campos” from the album Rican/Struction is a tribute to the Puerto Rican patriot Pedro Albizu Campos. Composed by Johnny Ortiz and arranged by Oscar Hernández, the song, sung by Adalberto Santiago, captures the feeling of Albizu’s resistance as he fought to liberate his homeland from foreign invading forces.

-

Albizu Campos was a jibarito, a legend who existed under the burning Puerto Rican sun. -

According to Adalberto Santiago, “the Rican/Struction album is a musical gem because, in New York, no musician buys records, and this one was bought by the entire salsa community.”

-

Dj. Augusto Felibertt y Adalberto Santiago

Vocalists for Ray Barretto and La Típica 73

- Adalberto Santiago was in Ray Barretto’s band from 1966 to 1972. When he left to join La Típica 73, he was replaced by Tito Allen, who recorded the album Indestructible with Barretto in 1973.

-

Tito Allen y Dj. Augusto Felibertt - When Adalberto Santiago left La Típica 73 to form Los Kimbos, his replacement in the group was once again Tito Allen. With them, Tito recorded the album Rumba Caliente (1976). Then, in 1977, La Típica 73’s vocalist was the late Camilo Azuquita for the album The Two Sides of Típica 73.

By:

Los Mejores Salseros del Mundo

Also Read: Raymundo “Ray” Barretto Pagan was born in Brooklyn, New York on April 29, 1929

How to make money today as a recording artist with record labels and digital platforms

Israel Tenenbaum Interview: The Changing Music Industry

The music industry has evolved, and artists’ income streams are no longer limited to album sales. Today, an artist can monetize their work in multiple ways, with or without the support of a record label and digital platforms.

Israel Tenenbaum (Los Angeles, California) is an American pianist, arranger, and music producer with a notable career in salsa and Latin jazz. He has worked with renowned artists and has lived in several countries, including Puerto Rico and Colombia.

1) What is the current process for recording, music production, and royalty distribution for Mr. Tenenbaum?

Well, let’s see. You’re talking about the current recording process, which is essentially the same, but it’s now generally done remotely. We grew up with recording environments where we would gather everyone (the musicians) in one place and record everything there.

But with remote recording capabilities, many musicians are now very well-equipped and they record at home. You can also take advantage of this because it gives you access to other talents, beyond the local environment you’re in. They don’t compare to what a musician or band leader might have locally, or for finding other guests, and so on.

So, remote recording is definitely in operation. I’ve been working with remote production for a while. In fact, it was pure chance that about six or eight months before the pandemic hit, I had just moved to California and I started to solidify and organize my global network of musicians, recording studios, producers, and a bunch of arrangers, and so on.

And when the pandemic hit, I was ready because I had already organized everything. Everyone thought it was a 90-day vacation. After 90 days, they thought, “Well, it’ll take a little longer.” And by the time they realized it was going to be a long haul, six months had already passed. It took them almost six more months to get organized themselves.

It was advanced, pure chance. And so that served me a great deal. And currently, I have that very solidified. I work with a dozen cities in seven countries. Thank you, thank you.

How does royalty distribution work? Does that still exist?

Yes, royalties still exist. What has changed dramatically is the way royalties are generated.

Let me explain it very simply. When we lived in the era of the physical product—which was what sold the most, whether it was the LP or the CD—you might earn 7, 8 cents per song on each copy in the U.S. If you wrote all your compositions and recorded all your compositions and recorded 10 songs on your album, you would automatically get 8 cents for each song on every album sold. So if you sold, say, 10,000 copies, that’s 10 songs at 8 cents, which is 80 cents per album. Then you have about $8,000, more or less. And on top of that, you have royalties because you’re selling the album. The album has two sources of copyright: the recording itself.

The owner of the recording has one royalty, and the composer has a completely separate royalty. So, these are the royalties you earn money from through sales, usually.

So, the record label would give a piece to the artist, say, 10%. That’s a huge royalty. And has that changed today? Nowadays, that hasn’t changed. It’s still between 7 and 15%, maybe 20% if you’re a superstar, but it’s more or less the same, somewhere between 7 and 12%. The difference is that now, that’s not what’s selling.

So this hasn’t completely changed because it was one thing to earn 8 cents every time your song was sold. Those were very easy numbers. If I earned a dollar for the compositions and then I earned another dollar or two more from the album sales, that’s three dollars per album. And if it was 10,000 albums, it was thirty thousand dollars. Simple as that. Now, it’s not like that. Now you’ll be paid thirty thousand dollars at a rate of approximately a third of a cent.

2) What is the impact of digital platforms that artists use to place their music?

Of course, for Israel, the use of digital platforms is almost inevitable because that’s how music is being distributed.

So, there’s a certain “democratization” in a sense—there’s easier access to that distribution—but the thing is, thousands and thousands of songs are uploaded to platforms every day. So, you’re competing with hundreds of thousands and millions of people, artists, and songs that are being uploaded all the time. And you have to compete with that to be found among those millions of people who are all competing for the public’s attention.

So, there are some interesting impacts. For example, it forces those who are really looking to build a career to think of themselves as a business from a promotional standpoint. “What do I do to promote my music? How do I get afloat? How do I show myself? How do I stand out from the crowd to get noticed?”

So that’s one thing that happens with artists. The artist really just wants to create, so part of the impact is an additional burden that takes artists away from their creative space. They have to spend a lot of time worrying about whether they’re getting plays, whether the numbers are moving, whether they’re being heard, how they can promote, whether to invest money in promotion. I mean, there are a lot of scattered impacts. It’s a loaded question with many answers, depending on the act you’re listening to and what you’re looking at.

The impact is certainly very strong… there’s access, and as an artist, I can reach and distribute my music so that it’s accessible to a large number of people that I didn’t have access to before.

Of course, it forces me to make a much bigger effort to try to stand out in that environment, among so many others who are competing for listeners’ attention. The royalties don’t really justify all the effort; they don’t pay for the effort.

The album, the music, and the recording have always been a promotional tool for the artist itself. It has never been a major source of income, but at least before, there was a system where the possibility of a real income existed. Now it’s practically nil.

So, there are a number of things behind that loaded question.

3) How is income distributed once the product is finished? How is the distribution? You already explained it in the first question, but a little more in detail.

It depends on the arrangements, the agreements the artist has. If it’s a solo artist, they’re hiring other people to come to the studio to record their album. So, those people are working on a commission basis, and they don’t have any other benefits beyond the payment they receive for coming to do the recording.

But it could be a group, a band, and in that group, they divide what the group generates, what the recording generates, into equal parts, let’s say.

It depends if you’re with a record label or a performing rights organization. I don’t remember what it’s called in Venezuela. In Colombia, it’s called SAYCO. In the United States, it’s called ASCAP or BMI (here in Venezuela, it’s SACVEN). Correct, SACVEN.

So, how that distribution is made depends on many factors. But in general, let’s say that the distribution platforms, which are the most widely used means today for artists who are 90 to 95% independent, use these distribution platforms that are aggregators. They put your music and distribute it to Spotify, iTunes, etc., etc., all the others. They collect money and pay you normally between 80 and 100% of what it generates. That also generates other income; it generates author’s rights that are paid directly from the platform. That is, Spotify pays for author’s rights. So it pays two types of royalties: one is for the composition and the other is for the recording. So for the composition, it pays one amount of money, and for the recording, the performance, it pays another amount depending on how that platform is organized.

For the copyright, they pay for the performance of the album because it’s considered a sale.

At the moment, what’s the difference between platforms and radio? You’re listening to the radio, and you can’t choose what’s going to play. You’re at the mercy of the DJ or the programmer or the radio station and the playlist that person has made, and you’re bound to what they chose to play.

On platforms like Spotify, you can listen to a playlist, but if you want to skip a song, you skip it, and if you want to repeat it, you repeat it, or you can make your own playlist.

So, if you have control of the recording and you can arrange it, when that happens, it’s considered that they have to pay a royalty as if it were a sale. A different royalty is generated, which is different from what happened, for example, with Pandora. Pandora was basically sitting and listening, and you could give Pandora information, telling it, “I like this music more,” or you’re listening to a playlist. Perfect. Besides that, well, that’s basically it, and obviously, anything that sells physically, because it’s still selling, and vinyl and LP sales are increasing. That’s back in style and is growing.

CDs are still being made. There is still a CD market, depending on the music you make, but there is a market, for example, for Latin music, for jazz. Something moves in Japan and China, but in Japan and some European countries, the CD still moves in a real way.

4) Name some current business models. You as a producer.

Let’s say there are several possibilities of what can happen. I can work as a producer, I can work with an artist strictly on the production—a business model where the artist is completely the owner of their own work.

As the owner of the LatinBaum Records label, I have to manage and participate directly with the artist. We cover costs and make investments alongside the artist to produce and promote the music in exchange for an equitable distribution of the profits.

The big record labels, the multinationals, are working with artists on what are essentially called “360-degree contracts” in which the record label is involved and has a piece of all professional activity, including merchandise such as hats, t-shirts, mugs, pens, whatever. As a record label, I get a piece of what’s sold in souvenirs; that’s marketing. Also, the work you do physically, meaning your events and presentations.

So, they control your book, they control your schedule, they control the artist’s schedule. They earn between 20 and 50% from the artist’s presentations, depending on the artist, their popularity, etc. And they also earn from composition royalties, they earn from album royalties, they earn from every angle.

Now, that business model depends on the investment that each party is willing to make. As they say in Colombia, “you eat rarer.” In other words, it depends on the circumstances of the moment, the artist, a number of factors. There isn’t just one business model that works now. You can also consider the artist doing everything themselves.

That’s another possibility; the artist has to set up their entire production infrastructure, etc. That’s another matter. It’s more complicated because the artist has to understand that their career and their art are now part of a company’s assets. They have to think of themselves as a business and develop their own business model that works for them within their capabilities and what they’re willing to do and their knowledge, right? Above all, “How much can I do?” I’m a single person, so I can compose the songs, I can do the arrangements, I can make the sheet music, I can hire the musicians, hire the recording studio, do the promotion, design the ads, I can do the marketing, I can also sell myself as an artist for presentations. I also sweep the floor, I also make the coffee, and I also serve. Do you get me? I mean, there’s a point of being multi-talented.

Yes, but there’s a very important point where one, or the artist, feels this obligation or has the obligation to have to do so many things that they don’t do any of them well. This is where record labels still play an important role in helping to guide the artist and providing them with services at a moderate price or within the artist’s reach according to their sales, their popularity, the things they can do. And also, these independent labels play the role of guiding and helping the artist and making certain things easier for them because they have some infrastructure that makes the artists’ work a little easier. So, the record label hasn’t disappeared. What has disappeared is what never really existed, which is money. The musician is always fighting for a few bucks to be able to do things, and if they’re lucky, they find an independent label that’s willing to help and invest time, effort, and money in advancing and promoting their career.

But the matter of the dream of being “discovered,” that no longer happens. It no longer exists. The only one who discovers themselves is you, and it’s up to you to show yourself to the world and look for connections, look for opportunities, and for business.

5) What strategies do artists use to monetize their work in the digital environment?

The work that the artist has to do on platforms is definitely a matter of persistence. It’s about regularly posting and telling their story, showing their art, and sharing their art and the reason for their art with the public. We are trafficking in emotions. That’s what the artist does; that’s the currency. It’s about making those emotions known and moving them and telling your story so that people identify with your story, with your music, with your art, and become a support for your career.

The most important thing here is consistency, persistence, always being on top of it. It’s not about “I’m eating a fried egg, let me take a picture of the fried egg.” No. If that’s what moves you and that’s what moves your audience, then go for it, but that’s not what it’s about.

People sometimes confuse being regularly present with having to take selfies all the time, and pictures of their food, and a picture of the neighbor’s dog, and “I’m laughing, and I already put on some crazy pants,” and so on. It’s not that. It’s about sharing your personality with the public, and to the extent that you, as an artist, define it, you should do it regularly. That’s on one hand. On the other hand, advertising is key. You have to invest in advertising.

Someone once spent about $30,000 on a production and went to several record labels, and none of them wanted to buy it. They didn’t want to take the product. Finally, they told one record label, “I’ll give you the album for free. You don’t have to give me a dime in royalties. I’ll sign the contract, but please release it.” The obligation and the commitment here are for you to release the album. And they didn’t take the money. Why? Because a production that costs $30,000 still has a cost of $60,000 or $80,000 that needs to be put into promotion for it to be heard, for it to sell. That’s what it is; that’s what they say.

That’s why it’s so hard for the small musician or artist to compete with the big stars, because they have enormous budgets with which they can produce their work, and the small one can’t compete. That’s why consistency is important, because it’s a way to promote and advertise yourself in a way that is, shall we say, theoretically free, right? It’s at your fingertips or has a very low cost, and if you do it constantly, you gain a space.

But you definitely have to invest money in advertising and promotion. There’s nothing like running an ad and telling everyone on a massive scale, “Here I am, here’s my product, this is my music.” At the end of the day, it’s like selling a can of beans; it’s the same thing. You have to put a good label on it; you have to run an ad on television, in the newspaper, on the radio, whatever it takes to sell your brand of beans. It’s that simple.

When you’re in the recording studio, 90% of what you do is art, and 10% is profit, plotting the commercial side, the hook. The moment the product leaves the studio, that’s inverted 180 degrees. It becomes 10% art and 90% commerce, 90% business, and what you have to do is take advantage of the tools.

Bonus Track.

6) What do you think about us Latinos creating a campaign to create a platform like Spotify, on a global level, so that musicians receive their royalties and money directly without going through other hands?

What do you think? Latin music, all Latin artists.

I think it’s a good idea, but what would be the purpose of… for musicians to have all the royalties directly without having to go through all that advertising, but to do their productions directly.

“Here’s the public, they stream it, and the money goes directly to the musicians, to you.”

Well, advertising cannot be avoided. How is the public going to find out that the music is there and that your music is available?

First of all, there has to be promotion, which can’t be avoided. One or two, you’re going to have to deal with all the Latin artists. The circumstances and conditions of your platform are no different from Spotify’s, or iTunes’, or any other. Why? Because you have to deal with different conditions that already pre-exist. That is, there’s a system that already pre-exists. All the music that is created and distributed, they have to deal with those predispositions. You have to deal with the SACVENs of the world, ASCAP, SAYCO, or whatever. You have to deal with the distribution chains; you have to pay either the author or you have to pay SoundExchange. You have to go through that whole procedure anyway. It’s exactly the same.

The idea is nice, but it’s utopian because there are systems in place globally, and you have to find that other formula to try to achieve what you’re proposing behind your question.

Thanks, Augusto. Likewise, I’m at your service for whatever I can help with. Blessings and greetings to the family.

Ralph Riley (Hong Kong)

Music Producer

1. The Recording and Production Process

When it comes to recording and production, the proper process involves capturing tracks for multitrack recording on tape or disk, followed by mixing and mastering. The technical complexity of the process is directly proportional to the number of tracks and artists involved in the production. Production costs and logistics also affect the final quality of the music produced.

Regarding copyright, it involves several key players: composers, publishers, record labels, and Performing Rights Organizations (PROs). Copyright royalties are generated from different uses of the song, such as streaming, physical sales, public performances, and synchronization in other media. It can be a complicated process that a lot can be written about and one that is constantly changing. The best advice is to do a lot of research or enlist the help of professionals who offer this consultation and/or full service for a fee.

2. The Impact of Digital Music Platforms

Digital music distribution platforms have significantly impacted how artists create, share, and monetize their music. They have democratized access to audiences around the world, providing opportunities for independent artists to bypass traditional gatekeepers and reach global listeners directly. However, this shift has also created challenges related to revenue generation and competition for visibility.

Here are some of the key challenges:

- Revenue Inequity: Streaming royalties are often perceived as low, making it difficult for artists to generate substantial income from streaming alone.

- Market Saturation: The ease of access to digital distribution has led to a highly saturated market, making it challenging for artists to stand out and get noticed.

- Competition for Visibility: Artists need to actively promote their music and engage with their audience to compete with the sheer volume of content available on these platforms.

- Dependence on Algorithms: Success isn’t solely dependent on the quality of the music, but is also influenced by the platform’s algorithmic recommendations, which can be unpredictable and require a strategic approach to navigate.

In conclusion, digital platforms have revolutionized the music industry, offering unprecedented opportunities for artists to connect with global audiences and build their careers. However, navigating the complexities of these platforms and finding sustainable income models remains a key challenge for artists in the digital age. This revolution, especially in the age of AI, continues to evolve rapidly.

3. Final Thoughts on Fairness

In summary, it seems to be always a little unfair to the vast majority of artists. It’s a complicated topic and I’d recommend a resource such as, for example, https://www.indiemusicacademy.com/blog/music-royalties-explained for better insights.

4. Popular Business Models

Some popular business models used in the music industry for record production include traditional record label deals, revenue-sharing models, and direct-to-fan approaches. Sometimes, it’s a combination of these. Streaming services and digital distribution also play a significant role in the current landscape.

For example, the direct-to-fan approach can include:

- Direct Sales: Artists can sell their music directly to fans through their own websites, online stores (like Bandcamp), and social media platforms.

- Crowdfunding: Platforms like Patreon allow artists to connect with fans and receive direct financial support through subscriptions or one-time donations.

- Streaming Platforms: Artists can directly upload their music to platforms like SoundCloud, Bandcamp, and even Spotify and Apple Music.

5. How Artists Get Paid in the Digital Realm

Artists can typically monetize their music in the digital environment through streaming platforms, digital downloads, merchandise, fan subscriptions, live streaming, and licensing. Additionally, artists can explore opportunities in social media monetization, crowdfunding, and brand partnerships.

Here’s how the payment system works and the factors that influence an artist’s earnings:

The “Pro-Rata” Payment Model

Spotify doesn’t pay artists directly for each play. Instead, it uses a “pro-rata” model:

- The company pools all its revenue (from Premium users and advertising) into a common fund for a set period, typically a month.

- Spotify keeps a portion (about 30%), and the rest (around 70%) goes into a “royalty pool” for rights holders.

- An artist’s share of this pool is determined by their “stream share,” which is the percentage of their streams compared to the total streams on the platform during that period.

Average Per-Stream Rate

While there’s no fixed rate, many sources estimate the average payout to artists on Spotify is between $0.003 and $0.005 per stream. This means an artist would need approximately 1 million streams to earn between $3,000 and $5,000.

Factors Affecting the Payout Rate

The actual amount an artist receives can vary significantly based on these factors:

- Listener’s Location: Subscription prices and ad revenue vary by country. A stream from a user in a country with a higher subscription fee (like the US or UK) will generate more revenue than a stream from a country with a lower fee.

- Listener’s Subscription Type: A stream from a Premium subscriber is worth much more than a stream from a free user (with ads).

- Artist’s Deal: Spotify pays the rights holders (record labels, distributors, publishers), not the artists directly. The artist’s contract with their label or distributor determines what percentage of the royalties they receive. Independent artists who use a distribution service typically keep a larger percentage.

- Minimum Threshold: As of early 2024, Spotify requires a song to have at least 1,000 streams in the previous 12 months to be eligible to generate royalties.

In short, an artist’s earnings on Spotify aren’t a simple calculation. They are the result of a complex revenue-sharing system that is influenced by a global audience, different subscription types, and each artist’s specific contracts.

I also manage music production through cassiorecords.com

Also Read: Understanding the music business