The initial idea of bringing together the three great orchestras of the Palladium in this innovative “three-in-one” orchestra concept came to Mario Grillo more than two decades ago.

As early as March 3, 2022, the mambo heirs celebrated the coming of age of The Big Three Palladium Orchestra in New York. Twenty-one years after the establishment of this remarkable big band, the concert entitled Palladium in the New Millennium took place in a packed Lehman Center for the Performing Arts.

The first presentation of 2023 of the “three-in-one” big band and coinciding with the 100th anniversary of the birth of “El Inolvidable”, Tito Rodriguez, the South Beach Jazz Festival’s line-up opened its musical offerings on Saturday, January 7, 2023 with the concert entitled Mambo Night in Miami Beach. At around 8:00 p.m. The Big Three Palladium Orchestra took over the Miami Beach Band Shell when Mario Grillo, known in the music scene as Machito, Jr. kicked off the musical feast that awaited us, to the sound of Cuban Fantasy.

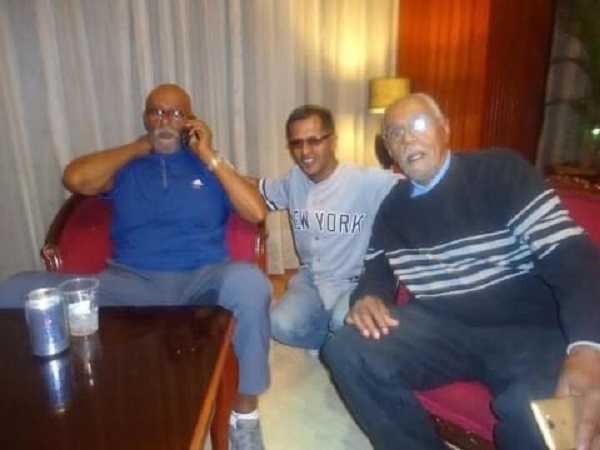

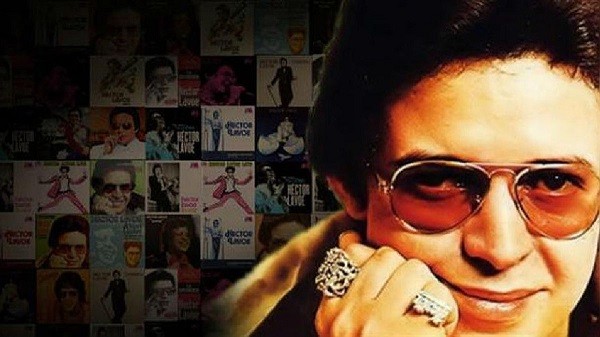

As you can see, each of the “big three of the Palladium” and owners of the mambo in its golden age inherited a timbalero son. These three bandleaders have made it their mission to keep the Palladium legacy alive and well. Although the mambo heirs have transcended the label of being the sons of the mambo owners, they do not forget that the Patriarchs are still a topic of conversation in musical circles around the world.

For the concert at the Miami Beach Band Shell, The Big Three Palladium Orchestra was joined by the veteran musicians: Carmen Laboy on baritone saxophone and musical direction; Jose Heredia on tenor saxophone, Mark Friedman on alto saxophone and flute, Julio Andrade on alto saxophone; Larry Moses, Seneca Black, Dante Vargas and Julio Diaz on trumpets; William Rodriguez on piano, Jerry Madera on bass, Daniel Peña on bongo and Diego Camacho on tumbadoras. On the vocal front, Sammy González, Jr. was backed by the coros of Starlyn Benítez and Tatan Betancurt.

The upscale repertoire vibrated and rumbled at the Miami Beach Band Shell, an elegant venue steps from the beach, which was filled to capacity.

Mario Grillo’s highlights were: Cuban Fantasy, Oye la rumba (La rumba), Ahora sí, Piñero tenía razón (Piñero was right), Babarabatiri (Babarabatiri) and Rumbantela (Rumbantela). On the other hand, Tito Rodríguez, Jr. performed the following songs: El que se fue, Cheveré, Yambú, Avísale a mi contrario, Agua de Belén and Fagot’s world. In the performance of Avísale a mi contrario, the conga of Diego Camacho and the bongo of Daniel Peña, who “quinteando a lo bravo” and adjusting to the tuning of the timbal in charge of Rodríguez, Jr. opened the way for the winds. And the winds entered through the wide door to increase the tempo of the night, which was already heating up to the sound of mambo.

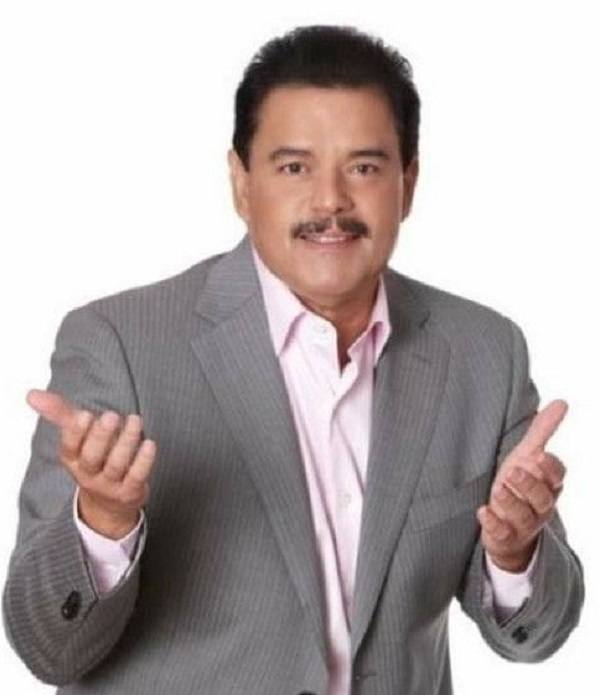

When it was Tito Puente, Jr.’s turn to play the timbal, he affirmed that Tito Puente was the pioneer in having a woman in the vocal front of an orchestra.

Then, preparing to close the first segment of the concert, he introduced Puerto Rican businesswoman and singer Melina Almodóvar, whom he backed for the performance of Mi socio.

The grand finale of the event placed the three timbaleros heirs of mambo in front of the orchestra to delight us with a masterful performance in sync with the rhythmic base that Diego Camacho and Daniel Peña did not hesitate to maintain.

Last year such a show was promised in which the heirs of mambo honor the legacy of their fathers on Puerto Rican soil. The show was to be entitled “Palladium in the new millennium” and was to be presented on Father’s Day at the Symphonic Hall of the Fine Arts Center in Santurce. However, it was cancelled.

I often say that the past is the past and the future is uncertain, so let’s hurry and wait for The Big Three Palladium Orchestra to perform in Puerto Rico.

I for one continue to live in salsa, which is still magic, fantasy and illusion.

Bella Martínez Writer, researcher of Afro-Caribbean music

You can read: Mike Arroyo the guitarist Using Jazz to praise God

Bella Martínez Writer, researcher of Afro-Caribbean music and author of Un conguero para la historia, Las memorias de Jimmie Morales.

787-424-8868