Virginia Ramirez, the talented concert pianist, pianist and singer-songwriter, has been making an impact for her contributions to the music of her country and the world. She was born in the city of San Cristobal, Venezuela and grew up in a family where art, poetry and music were the language of every day.

His mother was a poet (Etha, the Lady of Love), Dr. Enriqueta Martinez, his father Asdrubal Ramirez, a self-taught harpist, guitarist and singer of Venezuelan popular music.

Since she was 7 years old she plays the piano and from a very young age she began to develop her musical skills, she started her training at the Miguel Angel Espinel School with the well-known teachers Edgar Vasquez (Piano) and Heliodoro Contreras (Theory and Solfeo).

She graduated as a pianist, concert pianist and piano teacher at the National School of Music in Havana (Cuba) where she graduated with the highest qualifications and studied at the José Lorenzo Llamozas School and the Simon Bolivar Conservatory of Music.

He has taken courses in harmony and improvisation with professors Gerry Weil, Andres Alen Rodriguez and Mike Orta at the “FIU of Miami” in the jazz department.

Ramirez studied classical piano with Professor Igor Lavrov, recorded her jazz projects with drummer Willy Díaz and bassist José Velázquez in the “Jazz” program of the Venezuelan TV channel “Venezolana de Televisión” in Venezuela on several occasions, and her first album “Espiral de Fuego”.

She participated as a special guest of other groups such as Alberto Borregales and Fredy Roldán and El grupo la Calle.

She participated with a new proposal as a composer and pianist in important Jazz festivals in Venezuela as the “Latin Festival” of the Teatro de la Opera de Maracay (June 2003) and the “Prehot” of the 5th.

Festival de Jazz del Hatillo (October 2003), where he alternated and shared the stage with the American bands of Aaron Thurston (drummer) and Jaime Baum (flutist), receiving excellent reviews from the radio and television press.

She alternates her activity as a jazz concert performer with teaching, as a piano and singing teacher.

In her music school Vicky’s harpsichord.

Her formidable work in music and composition is very beautiful and colorful, because in her proposal she has fused jazz and Afro-Venezuelan elements highlighting the values of Venezuelan and Latin American music and using a variety of drums such as the Culo’e Puya, Quitiplas, Clarines, Cumaco and Chimbangles combining them with the songs of the peoples of the coast of Venezuela making excellent personal harmonic contributions.

He has achieved a high musical concept that has been recognized in the continent and the world, for that incredible capacity to unite the idea of the concert with the characteristics of the Show and for that reason he contributes much more of the pure musical element in each one of his performances.

With a rich repertoire and an unparalleled originality in the world of Venezuelan Female Jazz, this excellent artist is a source of joy and an excellent contribution to the new generations of Jazz.

She has won countless national and international awards and recognitions, among which stand out: World Prize “César Vallejo” for Artistic Excellence, World Prize “El Águila de Oro” for Artistic Excellence 2022, 2023, almo Chispeante prize 2024, awarded by the UHE, world Hispanic writers union, thousand minds for Mexico, and world academy of literature, history, art and culture First Mention in the Juan Sebastián Bach Competition in Havana Cuba.

1993 as a teacher, pianist, concert pianist has participated in various festivals and concerts such as the Fitztrovia Festival in London, in Mexico, Madrid, the south of France, in Colombia with his salsa group tabaco latino, where he performed in different cities, Cali, Bogota and Medellin.

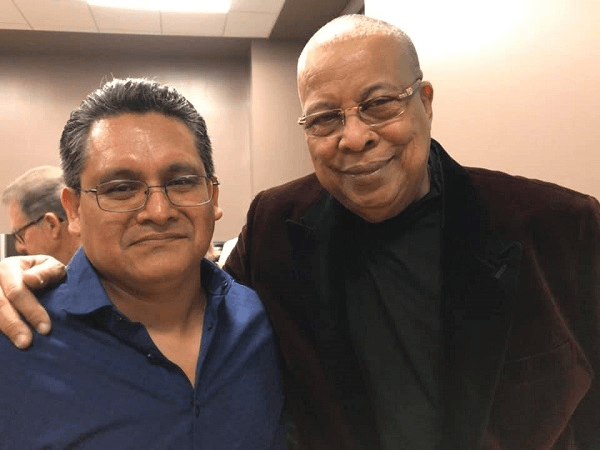

Within the salsa accompanied artists such as: Cheo Feliciano, Hernán Olivera, Meñique Lena Burke the singer Alfredy Bogado of the Venezuelan group “La Calle” and precisely with this group La Calle in the Juan Sebastian Bar when she worked there in 2000 was where they began their activities with salsa in several cycles of pianists, composers and arrangers.

In the Keyboard Museum of Caracas, in a jazz trio with Nene Quintero and William Velázquez on bass, in the Festival a toda Música Caracas, in the opera theater of Maracay and the Simón Bolívar University, among others.

Excellent comments in the national and international critics, have generated the presentation of his CD “Espiral de Fuego” presented by Otmaro Ruiz Jaquest Braunstein and Gerry Weil in his album “Manos y Alma” recorded, outstanding musicians such as: Nene Quintero, Aquiles Baez, Roberto Koch, Gonzalo Teppa.

Special guests: Vasallos del Sol, Aquiles Baez and C4 trio. This album “Manos y Alma” was presented by Aquiles Baez, Luis Perdomo and Pablo Aguirre from the BBC in London, received excellent reviews from the press in the south of France.

Her performance in the church La Canourgue in the south of France accompanied by the musicians Didier Hennot and Tonny Margalejo and her tour of successive concerts, carried out in France in different cities Mende, Saint Privat Des Vieux, Lozere, Ispagnac presenting her albums mentioned above.

She participated in the assembly and production of the play Cabaret with important theater artists such as Francis Rueda, Cayito Aponte, Natalia Martinez, Adrian Delgado, Karl Hoffman, Luis Fernandez performing in the Rios Reyna hall of the Teresa Carreño in different cities of Venezuela.

Virginia had the luxury of playing keyboards in the Kit Kat Club Band directed by Armando Lovera.

Great impact had her album “jazzguinaldos” produced as a trio with musicians Gonzalo Teppa and Nene Quintero, including as special guests Enio Escuariza, composer of all the lyrics of the album.

Her project “Acro Jazz” opens the horizon towards the world of circus arts, performing in different cultural centers of Venezuela musicalizing with the piano circus works and participating herself as a circus artist with the artist Jesús Piña in a pulsating work in the museum of the keyboard, Trujillo, Valencia among other cities with a new band integrated by Rubén Rebolledo Guitar, Willy Díaz Drums, David Rubio Bass and as special guests Jesús Piña and Kerlly Garcia.

He performed in the city of Morelia and Mexico, founded in 2015 a trio with musicians Fernando Mendoza Drums and Flavio Meneses bass, presenting the music of his albums in different nightclubs like Amati, Café de las Rosas, Casa de la cultura de Uruapan, and other cities of Morelia.

She accompanied drummer Antonio Sanchez in the house of music in Morelia.

Virginia Ramirez has collaborated with different artists of the Venezuelan music scene such as the group Facundo Project a Venezuelan Rock group, the singer Cheo Linares in his album “llegó la Navidad”, the singer Amarilis Bolaño in her album singing Henry Martinez, the singer Alejandra Gonzales in her album “Joyas de mi País” in the album “Tierra Liberada” and in the project “Venezuela demo”.

Ramirez has made music a matter of life and in her habitat of pianist and concert pianist, prepares for this year a vast plan to musicalize the poetry of the greatest poets of the world and a program entitled “La Totalidad de Virginia Ramirez”, by Cabina 11, Canal Global de Queretaro, Mexico, a country that has already known of her beauty and great talent.

I see in Virginia Ramirez, the complete artist with infinite talents as a pianist, singer, composer, songwriter and circus artist, who intentionally projects herself, illuminating the artistic firmament of the world with daring and magical projects that will always surprise the audience and make them feel the desire to ask for more.

Undoubtedly Virginia Ramirez is the artist of the XXI century, the princess of the piano and voice, the hope that will save the new generations of anti-music.

Dr. Carlos Hugo Garrido Chalem president of mil mentes por México and of the UHE Hispanic World Writers Union. President of the world academy of literature, history, art and culture.

Also Read: Wilmer Lozano from a very young age his mother saw in him the desire to be a musician