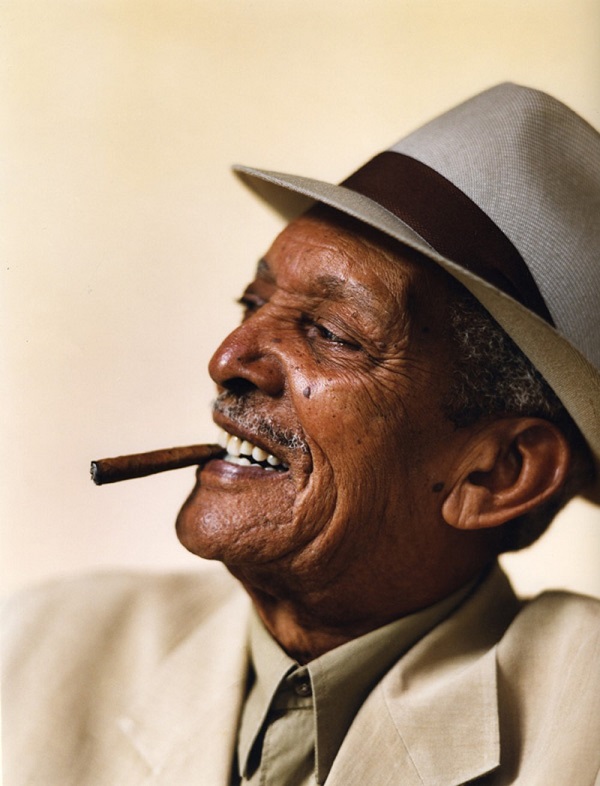

Máximo Francisco Repilado Muñoz better known as Compay Segundo (1907-2003) The voice that conquered the world in the nineties.

Máximo Francisco Repilado Muñoz, globally known as Compay Segundo, is one of the most emblematic and essential figures in traditional Cuban music.

Born on November 18, 1907, in Siboney, Santiago de Cuba, his life was a dedication to music that culminated in a late, but well-deserved, global fame before his passing in Havana on July 13, 2003.

Origins and Musical Training

Compay Segundo was raised in a highly musical and manual environment. His father, Máximo Repilado, was a bricklayer and a great lover of traditional santiaguera music, while his mother, Caridad Muñoz, provided a strong cultural influence.

Coming from a large family, his brother Lorenzo Repilado was also an active figure in the Santiago music scene.

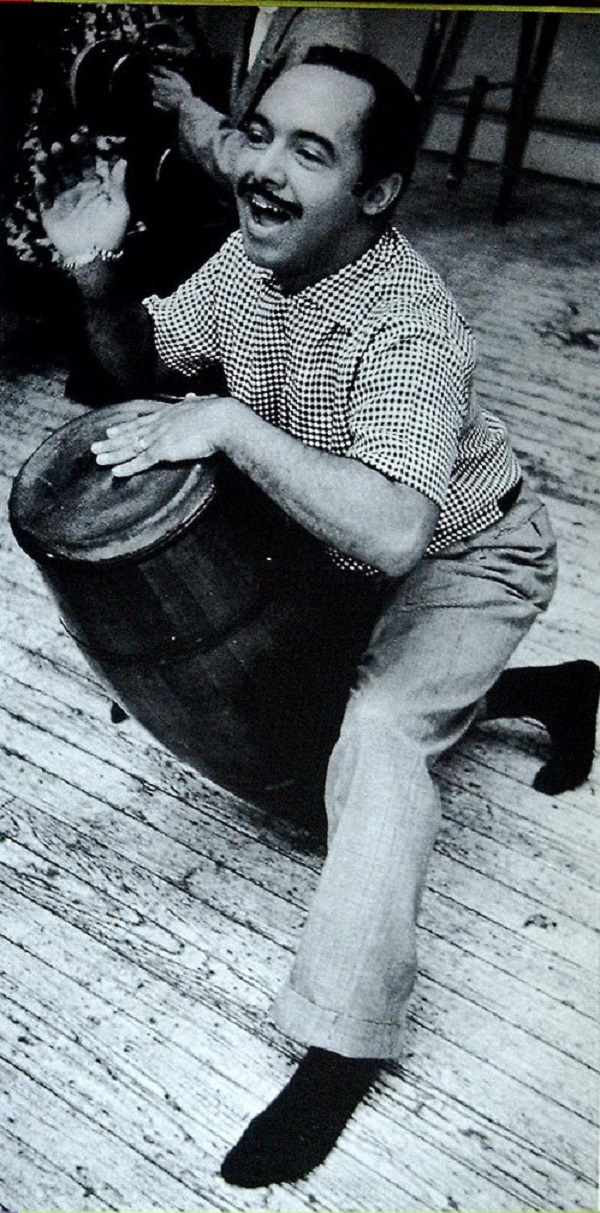

His beginnings were typical for the era. Compay started his career as a clarinetist in the Santiago Municipal Band, consolidating his training by later joining the Army Band. In the 1930s, he migrated to Havana, a crucial step that fully integrated him into the capital’s professional circuit.

Los Compadres and the Birth of the Name

The stage that would give him his artistic name and national fame was the formation of the Dúo Los Compadres in the 1940s alongside Lorenzo Hierrezuelo.

- The Nickname: The name “Compay Segundo” (Second Compadre) arose because Máximo Repilado always sang the low harmonic or “second” voice (segundo) in the song, while Hierrezuelo performed the main voice. Hence, the affectionate Cuban diminutive “Compay” (short for compadre) plus “Segundo” (Second).

- National Success: The duo became a sensation throughout Cuba, leaving behind unforgettable classics of son oriental such as “Macusa,” “Mi Son Orientál,” and the early version of what would become his most famous song: “Chan Chan.”

The Armónico: His Instrumental Contribution

One of Compay’s most unique contributions was the invention of the “armónico,” an instrument he designed himself. It is a seven-string hybrid, halfway between the traditional Spanish guitar and the Cuban tres. This instrument allowed him to simultaneously execute bass lines, harmony, and melody, creating a unique sound that became the foundation of his style.

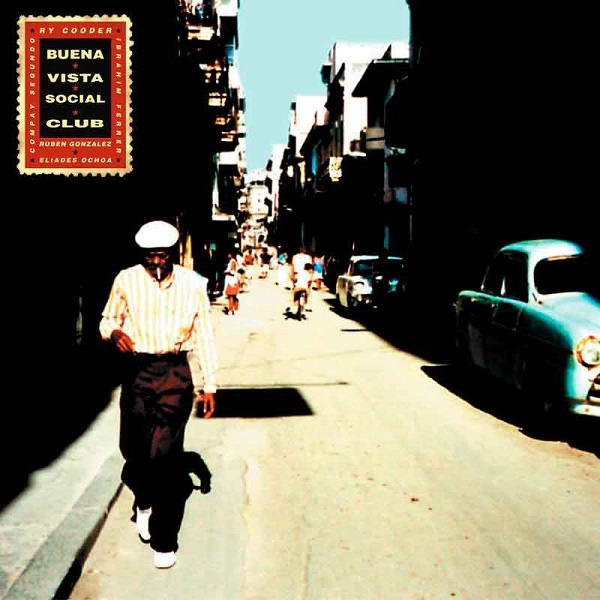

The Buena Vista Social Club Phenomenon

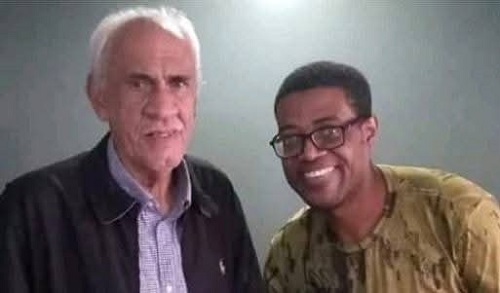

When it seemed Compay’s career was waning, destiny reserved the most glorious stage for him. In 1997, at the age of 90, he was invited by American musician Ry Cooder to participate in the recording of the album “Buena Vista Social Club.”

- Global Fame: The success of the album and the subsequent documentary directed by Wim Wenders catapulted him to worldwide fame.

- The Anthem: His unmistakable voice and the magical rendition of the song “Chan Chan” turned him into an international superstar, leading him to perform on the world’s most prestigious stages and bringing Cuban son to audiences of all ages.

Legacy and Family Continuity

Compay Segundo left behind a repertoire of songs considered national treasures. His most prominent tracks include “Chan Chan,” “Sarandonga,” “Las Flores de la Vida,” “Orgullecida,” and the popular bolero “Veinte Años,” which he popularized.

Compay was a father to at least nine children. His musical legacy not only lives on through his recordings but also through the activity of his descendants:

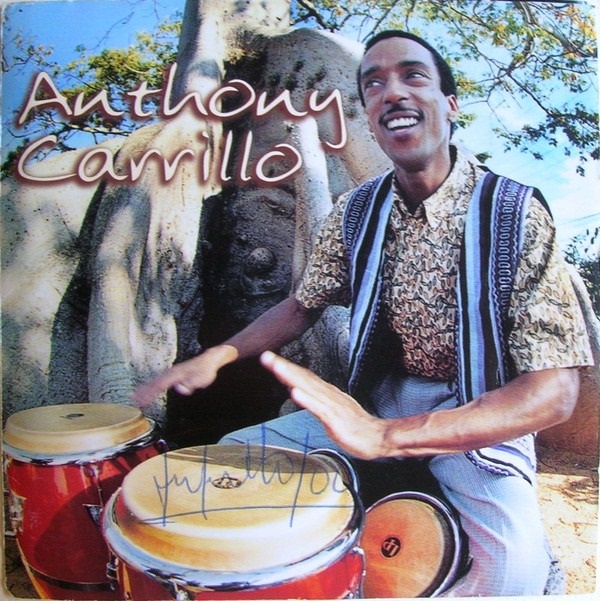

- Basilio Repilado (1954–2012): Founder and arranger of the Grupo Compay Segundo.

- Salvador Repilado: Upright bass player and current director of the Grupo Compay Segundo, the official international touring ensemble.

Furthermore, the younger generations (grandchildren and great-grandchildren) such as Yohel, Alejandro, and Yurisley Repilado continue the tradition in Havana with the ensemble “Los Herederos de Compay Segundo” (The Heirs of Compay Segundo), ensuring that the unmistakable sound of the Patriarch of Cuban Son continues to resonate in Cuba and the world.

Collaboration: