Search Results for: Salsa

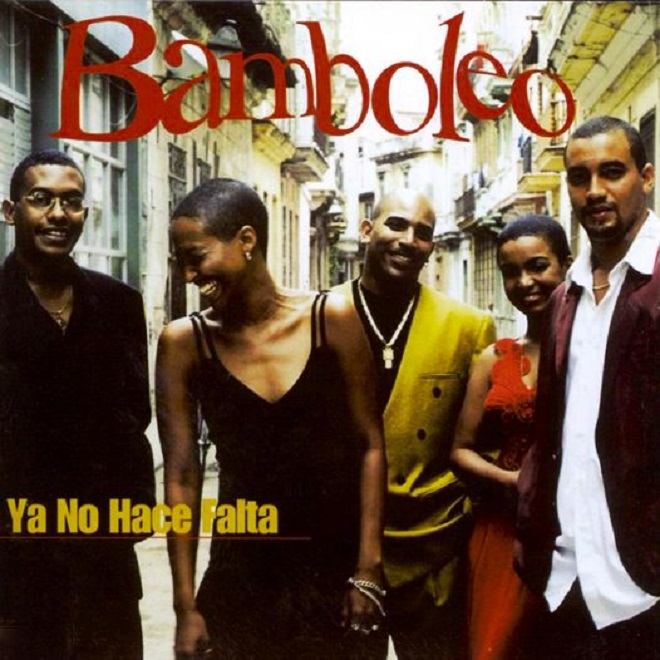

Bamboleo de Lázaro Valdés is another of those exquisite Cuban products, as well as sweet rum and mild cigars

Like the sweet rum and mild cigars, bamboleo is another one of those exquisite Cuban products that, once tasted, can’t get enough.

The 14-member timba group is a fiery number, from its music and choreography to its well-dressed singers and musicians.

Lazaro Valdes leads the group, plays piano, arranges, composes and writes songs. Born in Havana, he studied at the Alejandro García Caturla Academy in the 1970s.

He created Bamboleo after spending time performing with artists such as Pachito Alonso, Bobby Carcasses and Héctor Téllez.

He selected the best musicians and incorporated into his new company many who had been trained at the Escuela Nacional de Arte de La Habana.

He added sparkle with vocalist Haila Mompie, who in turn recruited vocalist Vannia Borges. Another Havana native, Borges began studying music at the age of five, and first sang professionally with an all-female group known as D’capo in the early 1990s. Four years later, she became part of the band D’capo.

Four years later, she moved on to Pachito Alonso y su Kini Kini, which she left in 1997 to add her talents to Bamboleo.

Guantanamera Yordamis Megret joined the group in 1998, a year after Mompie’s departure. She began her musical training at the age of 10 and took up the guitar.

Like Borges, she is also a student at the Escuela Nacional de Arte. After graduating, she began singing professionally with Ricacha. Before joining

Bamboleo, Megret sang in José Luis Cortés’ salsa group PG. Bamboleo began touring outside Cuba in 1996, the same year the group debuted with Te Gusto o Te Caigo Bien.

The group has performed in major U.S. cities from Chicago to Miami, and from New York to Los Angeles. Following the release of Yo No Me Parezco A Nadie and Ya No Hace Falta, the group toured the world, with stops in Europe, the United States and Japan, as well as the Heineken 2000 World Music Festival in China.

Bamboleo also collaborated on the Temptations’ Grammy-winning album Ear-Resistable.

In addition, the group has appeared on MTV’s Road Rules and has worked with artists such as James Brown, Femi Kuti and George Benson.

Bamboleo, one of the best-known groups on the crest of the timba wave, a new style that blends salsa with funk and jazz elements and emanates from the streets of Cuba, remains at the forefront with 1999’s Ya No Hace Falta.

After leaping to international notoriety with 1997’s Yo No Me Parezco a Nadie, the pressure was on to deliver for his newfound fan base.

With smooth arrangements and a band with a tight drum kit, Bamboleo had no trouble making good on their reputation and, if anything, raised the bar for the entire genre.

Both the horn section and the vocalists have a cool, smooth approach that contrasts with the energetic sound of similar groups like Charanga Habanera or NG la Banda.

This smoky, jazzy sensibility juxtaposed with the sharp corners of the superfunky rhythm section makes for easy and enjoyable listening.

The group doesn’t lack for warmth, with salty montunos from pianist/arranger Lazaro Valdes and plenty of time changes from a percussion section as good as any operating today.

Sonically, the ears rejoice in listening to a timba album that lacks neither fidelity nor modern production sensibilities.

With its balanced overall sound, unique approach and expert musicianship, Bamboleo will set trends and erase boundaries for decades to come.

Evan C. Gutierrez

Bamboleo – Ya No Hace Falta (1999).

Musicians:

Lázaro M. Valdés Rodríguez (Director, piano, composer).

Abel Fernández Arana (Alto Saxophone)

Carlos Valdés Machado (Tenor saxophone)

Anselmo “Carmelo” Torres (trumpet)

Dunesky Barreto Pozo (Congas)

Alberto Para (Maracas)

Herlon Sarior (Timbales)

Jorge David Rodríguez (Voice)

Yordamis M. Mergret Planes (Vocals)

- Frank Cintra Cruz (Trumpet)

Alejandro Borrero Ramírez (Vocals)

Vannia Borges Hernández (Vocals)

José Antonio Pérez Fuentes (Violin)

Maylin de la Caridad González Aldama (Cello)

Ludwig Nunez Pastoriza (Drums)

Rafael P. Pacerio Monzón (Banjo)

Ulises Texidor Pascual (Bongos)

Sources:

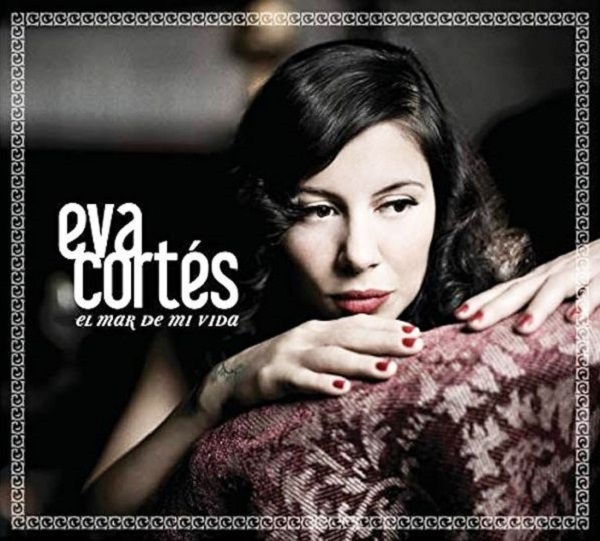

Eva Cortés at present, her music reflects the influences received from her cultural miscegenation

Fragile voice, delicate and powerful at the same time, that moves with devotion and good work through the multiple paths of jazz.

Eva Cortés, born in Tegucigalpa (Honduras), 1972, is a Honduran jazz singer and composer.

More than a voice, she is our jazz star in the world.

She is part of the fusion movement, incorporating in her music the influences of traditional Latin American music (zamba, bolero), blues, traditional Andalusian music and jazz.

He sings with a Latin American Spanish cadence and Andalusian echoes and accent.

He grew up in Seville and currently resides between Madrid and New York.

He became known in 1980 after recording an album of children’s songs entitled Cosas de niños with singers such as Ana Belén, Víctor Manuel, Mocedades and Miguel Bosé.

Nowadays, his music reflects the influences received from his cultural miscegenation, as well as from the different musical genres developed throughout his career.

Growing up in a family of great musical tradition, she was exposed to Latin American music. Although we hear in her first compositions, at the age of 16, a strong influence of blues.

In January 2006 she flew to Santiago de Chile to record and co-produce Sola Contigo, her first solo album, which was later mixed and mastered in Paris.

In this work we can find South American rhythms fused with jazz and a soft touch coming from the south of Spain.

Eva feels honored to have had the collaboration of musicians with great international prestige: Jerry Gonzalez,

Antonio Serrano, Pepe Rivero and Nono Garcia among others.

In April 2008 Eva recorded her second album Como Agua entre los Dedos, which is an album of original songs composed mostly by Eva Cortés, although they also stand out in the two Spanish adaptations of two standards such as You don’t know what love is and La Vie en Rose.

They released their third album El Mar de Mi Vida on April 6, 2010. With his personal jazz fusion, he has managed to carve a niche for himself among the most interesting and promising proposals of the Spanish jazz scene. [El Mar de Mi Vida brings together 12 songs that are maximum exponents of cultural crossbreeding.

On this occasion, in addition, the flamenco great Miguel Poveda joins in the version of the song C’est si bon, Perico Sambeat, Lew Soloff (considered one of the most brilliant trumpet players of recent times and who has collaborated with Marianne Faithfull or Frank Sinatra, among others), Santiago Cañadada, Rémy Decormeille, Georvis Pico, the electric bassist of the moment Hadrien Feraud and the English drummer Mark Mondesir (both musicians of John McLaughlin).

Eva once again signs most of the tracks and shares authorship in a couple of songs with Brazilian guitarist Kiko Loureiro.

In addition, we find tracks such as Alfonsina y el Mar (Ariel Ramírez-Felix Luna), Une chanson Douce (Henrie Salvador- Maurice Pon), C’est si bon (André Hornez-Henri Betti) and Que reste-t-il de Nos Amours (Charles Trenet-Leo Chauliac).

Eva Cortes – The Sea Of My Life (2010)

Tracks:

- The Sea Of My Life

- Casi

- C’es Si Bon / What’s Better? (Feat. Miguel Poveda)

- Desterrado

- Valsa Da Menina

- Remembering Tomorrow

- Little Matter If Later

- Que Reste-T-Il De Nos Amours / I Wish You Love

- Woman

- Alfonsina And The Sea

- Da Igual

- Une Chanson Douce

Information realized (January 13, 2024)

Sources:

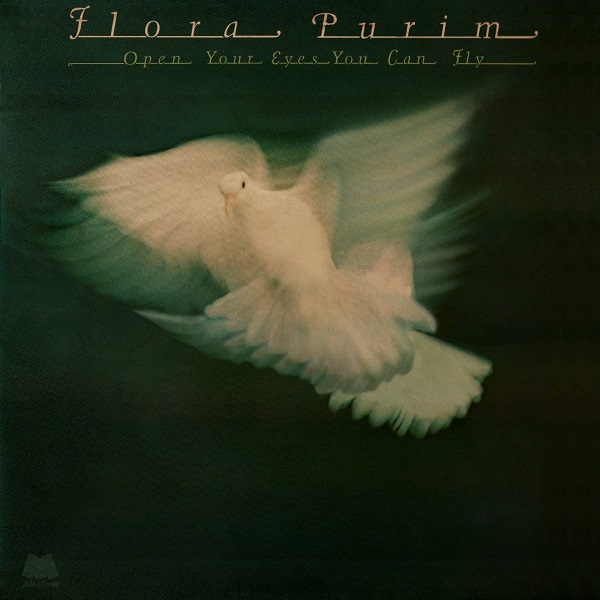

Flora Purim has earned her two Grammy nominations for Best Female Jazz Performance

Flora Purim (born March 6, 1942 in Rio de Janeiro) is a Brazilian jazz singer known primarily for her work in the jazz fusion style.

She was featured for her part on Chick Corea’s landmark album Back to Eternity.

She has recorded and performed with many artists, including Stanley Clarke, Dizzy Gillespie, Gil Evans, Stan Getz, the Grateful Dead, Santana, Jaco Pastorius, and her husband Airto Moreira.

Flora Purim’s voice has earned her two Grammy nominations for Best Female Jazz Performance and Down Beat magazine’s Best Female Singer award four times.

Her musical partners include Gil Evans, Stan Getz, Chick Corea, Dizzy Gillespie and Airto Moreira, with whom she has collaborated on more than 30 albums since moving with him from her native Rio to New York in 1967.

In New York, she and Airto became the center of the period of musical expression and creativity that produced the first commercially successful “Electric Jazz” groups of the 1970s.

Blue Note artist Duke Pearson was the first American musician to invite Flora to sing with him on stage and on record.

She then toured with Gil Evans, about whom she says, “This guy changed my life. He gave us a lot of support to do the craziest things.

This was the beginning for me. Her reputation as an outstanding performer earned her work with Chick Corea and Stan Getz as part of the New Jazz movement that also contained the nurturing influence of saxophonist Cannonball Adderley.

Soon after, Flora began to seriously re-educate discriminating musical minds after joining with Chick Corea, Stanley Clarke and Joe Farrell to form Return To Forever in late 1971.

Two classic albums resulted – Return to Forever and Light as a Feather nodal points in the development of jazz fusion.

Flora’s first solo album in the United States, Butterfly Dreams, released in 1973, immediately placed her among the top five jazz singers in Down Beat magazine’s jazz poll.

In the mid-1980s, Flora and Airto resumed their musical collaboration to record two albums for Concord – Humble People and The Magicians – for which she received Grammy nominations.

In 1992 she went further by singing on two Grammy winning albums – Planet Drum with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart (Best World Music Album) and the Dizzy Gillespie United Nations Orchestra (Best Jazz Album).

The launch of the Latin jazz band Fourth World in 1991, featuring Airto, new guitar hero Jose Neto, and keyboard and reeds leader Gary Meek, marked a new era in Flora’s career.

The band was signed to the British jazz label B&W Music, and Flora consciously set out to win over the next wave of listeners.

Flora’s 1995 album Speed of Light, with major writing and performance contributions from Chill Factor and Flora’s daughter Diana Purim Moreira, makes the connection between her experimental beginnings with Chick Corea and Gil Evans and the new “head” music being produced by jazz musicians in the London and New York hip hop scenes.

Flora Purim Open Your Eyes You Can Fly (1976)

1- Open Your Eyes, You Can Fly (Chick Corea-Neville Potter)

2-Time’s Lie (Chick Corea-Neville Potter)

3- Sometime Ago (Chick Corea-Neville Potter)

4-San Francisco River (Airto Moreira-Purim Purim)

5-Andei “I Walked” (Hermeto Pascoal)

6-Ina’s Song “Trip to Bahia” (Flora Purim)

7-Conversation (Hermeto Pascoal)

8-Medley: White Wing/Blank Wing (Hermeto Pascoal-Flora Purim).

arrangements:

Hermeto Pascoal (4.5.7.

Egberto Gismonti (4)

Flora Purim (6)

The whole group (1.2.3)

01-David Amaro – electric guitar

George Duke – electric piano

Alfonso Johnson – electric bass

Ndugu (Leon Chancler) – drums

Background vocals: Flora, David Amaro, George Duke, Hermeto Pascoal

Instrumental solo: David Amaro (electric guitar)

02-Hermeto Pascoal – flute

David Amaro – acoustic guitar

George Duke – electric piano, ARP sequence,

ensemble synthesizer

Alfonso Johnson – electric and acoustic bass – Alfonso Johnson – electric and acoustic bass

Ndugu – drums

Airto Moreira – percussion

Instrumental solo: Hermeto Pascoal (flute), Nudgu (drums)

03-Hermeto Pascoal – flute

David Amaro – electric guitar

George Duke – electric piano, ARP sequence,

ensemble synthesizer

Alfonso Johnson – electric bass

Ndugu – drums

Airto Moreira – percussion

Laudir de Oliveira – congas

Instrumental soloist: Hermeto Pascoal (flute), David Amaro

(electric guitar)

04-Hermeto Pascoal – flute, electric piano

Egberto Gismonti – acoustic guitar

David Amaro – electric guitar

George Duke – moog synthesizer

Alfonso Johnson – electric bass

Ron Carretero – acoustic bass

Robertinho Silva – drums

Instrumental duet: Hermeto Pascoal (flute) and George Duke

(synthesizer

05-Hermeto Pascoal – flute, electric piano

David Amaro – electric guitar

George Duke – moog synthesizer, clavinet

Alfonso Johnson – electric bass

Airto Moreira – percussion

Robertinho Silva – drums, berimbauduet

vocal: Flora Purim and Airto Moreira

Instrumental duet: Hermeto Pascoal (flute), George Duke (flute), George Duke

(synthesizer), David Amaro (electric guitar)

06 -Hermeto Pascoal – electric piano

David Amaro – electric guitar

George Duke – moog, ARP Odyssey and ARP Odyssey sequences, ARP synthesizer

ARP, ensemble synthesizer

Alfonso Johnson – electric and acoustic bass – Alfonso Johnson – electric bass and acoustic bass

Robertinho Silva – drums, percussion

Laudir de Oliveira -congas

Instrumental solo: Georrge Duke (ARP synthesizer)

Odyssey)

07-Hermeto Pascoal – electric piano

David Amaro – electric guitar

George Duke – ARP sequences ensemble and moog synthesizer

moog synthesizer

Alfonso Johnson – acoustic bass

Airto Moreira – percussion

08-Hermeto Pascoal – electric piano, pipe, harpsichord,

whistling, percussion (seven-up bottles)

Egberto Gismonti – acoustic guitar

Ron Carretero – acoustic bass

Alfonso Johnson – electric bass

Airto Moreira – percussion, drums, berimbau

Robertinho Silva – percussion, berimbauduet

vocal: Flora Purim and Airto Moreira

Instrumental solo: Hermeto Pascoal (harpsichord and whistle)

Information realized (March 28, 2008)

Sources:

Also Read: Samuel Quinto Feitosa is a Brazilian virtuoso jazz and classical pianist

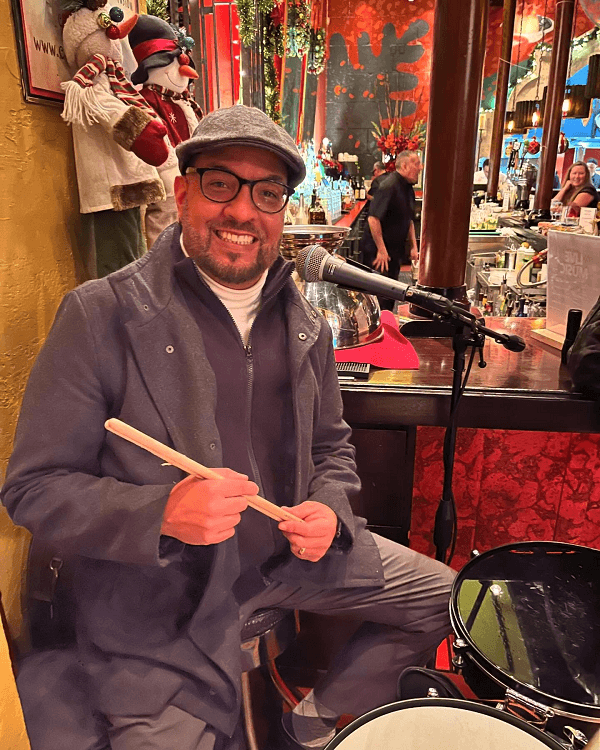

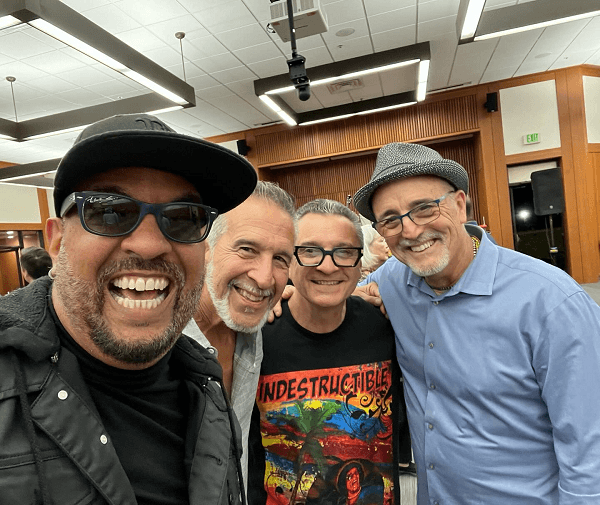

Career and interesting facts about Venezuelan singer and musician Omar Ledezma Jr.

Venezuelan singer, percussionist and music teacher Omar Ledezma Jr. has already talked to us in the past and has revealed important details regarding his life and career, but this time, our editor Eduardo Guilarte has been in charge of interviewing him and revealing some unknown details about his different facets professionally and personally.

Is such a pleasure to have the chance to talk to one of the most talented Latin musicians who currently lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and know so many things that the artist had not previously revealed.

Omar Ledezma’s beginnings in music and childhood

Omar Ledezma Jr. was born on February 17, 1972 in Caracas, Venezuela, and was raised in a very close family that gave him a lot of love and care since he was a child. Both the Ledezma and López families were very important in his growth, but it was from the Ledezma’s that he got his musical vein.

His mother and cousin José Vicente Rodríguez López decided to enroll him in the marching band at the Claret School, where he had his first contact with music by playing the snare drum, an instrument he was first assigned to play. It is also in the band where he started making friends with other teens who were already forming gaitas groups to compete in contests related to this traditional Venezuelan genre.

When he turned 16, he began to participate in these gaitas inter-school competitions in 1987 and 1988. In 1989, he participated in his first big musical event at the nightclub Mata de Coco. Omar assures that this was the official start of his career in a more professional way. A few years later, going hand-in-hand with his father, he began to take a deeper interest in music as a profession and wanted to experiment with other genres such as Afro-Cuban music and Latin jazz.

This path led him to join the orchestra La Charanga Clásica led by Mr. Frank Luzón. While playing there, he met several inspiration timbaleros such as Daniel Cádiz (from the Andy Durán Orchestra).

In parallel with all of the above, Omar was admitted to study in law school at the Santa María University, so he shared his time between his university studies and his professional musical activities. In his spare time outside the university, he played Latin jazz and was formed as a percussionist with his orchestra.

In 1995, Omar graduated as a lawyer as part of the class ”Honor a Venezuela” ranked in 12th place among his classmates. Although today he is not engage in law at all, he considers that having continued his studies was very important to him as a person because he would have a base on which to stand on in case his plans with music fell through.

However, the artist never thought about practicing law, since he was very clear that it would be difficult to do so due to the legal situation in Venezuela, so he continued to focus on his great passion, which was music. Besides, after analyzing it, he decided that he did not have a natural talent for that career.

In parallel, during those years as a law student, he made a trip to Cuba, which he claims changed his life completely. Some friends he made there, when seeing his skills as a musician, told him that he could be studying law, but that his life was and would be music forever.

The United States and Berklee College of Music

Just a few years after graduating, specifically in 1998, Omar made the decision to move to the United States looking for new opportunities and describes this trip as an exploring experience because many of his friends, orchestra fellows and acquaintances from the musical environment in general started taking new directions in the mid 90’s. The young man knew he wanted to do the same and chose the city of Boston to settle in at first.

Although he finally moved to Boston in 1998, already in 1997, his mother gave him the idea of going to the United States with an open ticket so he could decide whether to stay permanently or return. In the end, he opted not to use the return ticket and stayed in Boston to try to enter any music school through a scholarship.

After checking several options, he chose Berklee College of Music because it was the only college that allowed him to study composition and arranging as hand percussionist, so he auditioned to be admitted and was selected in the fall of 1999. He obtained a 70% scholarship, but he had to work hard to get the remaining 30%. In that sense, Omar assures that the same school helped him to obtain the corresponding permits to work legally in the country and thus be able to pay the percentage that is not covered by the scholarship.

Omar also told us that it was his friend Gonzalo Grau who helped him do the demo with which he auditioned to enter Berklee and it was a song of his own titled ”Cacao”. Today, he assures that that recording gave him one of the greatest opportunities he has ever had in life, which was to study there. He spent a total of four years studying in that institution and graduated in 2003.

During his undergraduate studies at Berklee, Omar had the option to study business and intellectual property and his lawyer’s training made it easier for him, but he defines himself as a ”natural born performer” and his life was the stage, so he did not see himself stuck in an office solving cases.

One of the first jobs Omar had in Los Angeles was replacing the singer from Johnny Polanco’s prestigious orchestra and that one that helped him take that place was Ray Barreto’s flautist, the late Artie Webb. The concert was held at the Mayan.

Family

As to the family part, Omar told us that he had married his wife Jennifer Radakovich about seven or eight years ago, but they have no children for the moment. This is because they are still analyzing their opportunities to settle permanently in the state of California, so he assures us that they are still building their future as a couple and as a family.

Jennifer’s family comes from Serbia and settled in Detroit, Michigan. They had to leave their country, which was then the former Yugoslavia because of the war that went on in the territory at the time. In fact, at a family reunion, his in-laws told him that his wife’s father arrived in the country on the boat anchored in Long Beach, California, The Queen Mary.

Pacific Mambo Orchestra

Omar Ledezma started his journey with Pacific Mambo Orquesta practically since its foundation in October 2010, when he started playing at Café Cocomo. Santana’s timbalero Karl Perazzo, who was already included in the lineup of the venue, proposed him to go to this place to play as a percussionist on Monday nights. The problem was that there was no money to pay him for the moment.

That’s when the directors of Pacific Mambo, Christian Tumalan and Steffen Kuehn, proposed to the owners of Cafe Cocomo to give them some space to have band practice. These Monday meetings ended up being paid rehearsals open to the public in exchange for 10 dollars a night. This lasted some years in which the 20 members of the orchestra were in charge of developing much of the repertoire that has made them famous internationally.

About this time, Omar said that, on several occasions, he and his orchestra fellows sat down to talk about the continuity of the band owing to the lack of money. The wonderful thing is that everyone always voted in favor of their stay in the group despite the adversities. According to the Venezuelan musician, it was this hunger and desire to succeed that made the orchestra what it is today.

These efforts worked and Pacific Mambo Orquestra managed to win their first and only Grammy so far in 2014. That year began with the orchestra’s appearance in one of the main banners of the iTunes page for a little over a week, which gave them a lot of popularity at that time and was not common for Latin artists and groups.

That same year, the group began touring with Tito Puente Jr. in August and were so successful that Omar and five other members of the group decided to begin campaigning for that year’s Grammys via e-mails to all the members of the jury promoting their latest album. Then, on tour, they received the news of their nomination (the second of Omar’s career), but they did not think they would win.

Much to the surprise of Omar, in January 2014, he received word that Pacific Mambo Orquesta won its first Grammy in the category of Latin Tropical Album of the Year. This event changed the lives of everyone in the group to the extent that large media outlets started looking at them. One of them was world-famous Billboard magazine, which published a piece talking about the band and its talents.

It is important to stress that, although it was an experience the musician will never forget in his life, he is aware that this is in the past and has to look ahead and focus on his future successes. At this moment, Omar and his companions are focused on making up for time lost during the pandemic and performing all the activities that confinement prevented them from doing.